S.O.S: Save Our Soil

Just don’t call it dirt.

“That’s what’s under your fingernails. Soil is what grows your food that keeps you fed,” USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service soil scientist Shawn Nield tells elementary school kids at workshops that let them dig a little deeper into the stuff of life.

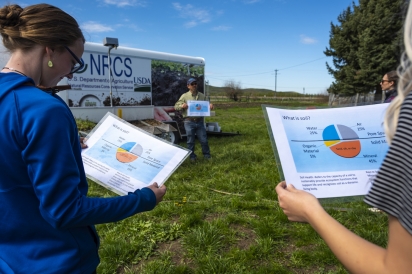

“There is a lot to talk about,” Nield says as he unpacks soil samples and the tools he needs to create a mini Dust Bowl replica from a trailer he tows across the state.

The lessons that spill from the traveling classroom that visits schools, community events and farms with workshops and hands-on SOIL 101 discussions not only examine the microbes living in what lies beneath our feet but reveals why what some of us simply, incorrectly and very unscientifically call “dirt” is so worth conserving.

Many of us go to great pains to eliminate dirt from our lives. But soil—that’s what we want to save.

“With some straightforward soil health measures, we could save our soil resources. Ultimately the goal of the NRCS is to conserve soil resources to provide food and fiber for generations to come,” Nield says.

And Nield knows that once people get a good look at soil, they’ll understand the importance of that conservation.

“Most people don’t get a chance to look at what the soil appears like below the surface,” says Paul McDaniel, professor of soil and water systems at University of Idaho.

That means most people miss out on the chance to take a close look at the earth that keeps them alive.

“It’s where the action is,” McDaniel says as a backhoe digs a four foot deep trench bordering fields of lettuce and early vegetable shoots at Fiddler’s Green Farm in the Dry Creek Valley north of Boise.

Black, rich soil spills from the mouth of the backhoe, revealing foot upon foot of dark strata teeming with the spoils of organic life and life-sustaining potential. McDaniel also sees an interplay of ecological forces that unites geology, climate studies, biology and hydrology into one big, geekable backhoe scoop.

“Soil is the intersection of the atmosphere, the lithosphere, the hydrosphere and the biosphere,” he explains.

Each dig unearths a bit of coffee-ground-colored geologic history and opens the ground so ecophiles at a spring NRCS workshop can better understand the look of good soil stewardship and learn that a healthy landscape requires much more than fertilizer and water.

“A combination of the location in the valley, climatic factors, and I suspect having access to irrigation have made these really good soils,” McDaniel says of the ground that sustains the crops at Fiddler’s Green.

“This has really high organic material, which indicates a really high functioning soil in the region,” he says.

Farmers in the Dry Creek Valley can thank good luck, Mother Nature and the stewardship of previous generations for the black gold that helps stock Boise-area farmers markets, grocery stores and restaurants. It’s an area that maintained much of its agrarian ethos since the late 19th century when settlers stumbled onto the region and planted Boise’s first bread basket. But large tracts of highly productive Dry Creek farmland face threats from large-scale proposed development, residential activity and neglect.

But for a moment on a warm April afternoon, soil enthusiasts peered into a four-foot-deep trench to view soil perfection.

Fiddler’s Green farmers Alex Bowman-Brown and Justin Moore inherited pristine soil from previous generations, but their stewardship and farming practices continue to keep the earth healthy and bountiful. Mounds of manure and compost sit at the end of a field and on uncultivated parcels, grasses cover naked ground. Those are just a few elements that workshop participants learn remain vital to keeping soil resources from turning into Dust Bowl dirt.

These lessons include the importance of keeping soil covered with natural grass or a cover crop to prevent water loss and erosion; and the significance of keeping living roots on the ground, minimizing soil disturbance, diversifying crops and introducing compost or livestock to farmland.

“Livestock are really good at restoring nutrients to the process. It’s got some advantages over commercial fertilizers,” Nield says.

Many of Nield’s tips align with ideas swirling around regenerative agriculture, an approach to conservation and farming that aims to reverse climate change by building soils and restoring depleted earth with biodiverse landscapes that can pull carbon emissions from the atmosphere and conserve water.

Between one-third and two-thirds of soils on the planet have already been degraded, and without conservation measures Nield says we risk losing our fertile landscape to the blights of erosion, water loss and degradation, which can turn soil into the stuff of its very different and very distant cousin, dirt.

“As far as I know, ours is the only society that uses the words “dirt” and “soil” interchangeably,” McDaniel says. “In other cultures and languages, when they’re talking about what we think of as dirt, they’re talking about filth,” he says.

The word “dirt” derives from the Norse word “dirt” which translates into “shit.” The etiology of “soil,” on the other hand, remains firmly rooted the Old French world “souel” meaning place, ground or earth.

“We use them like they mean the exact same thing and they really don’t,” McDaniel says.

But without soil conservation, soil can certainly become dirt.

USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service

Paul McDaniel

University of Idaho | @uidaho

Fiddler’s Green Farm | @fiddlersgreenfarm