A Farm to Table Community: Summer 2018

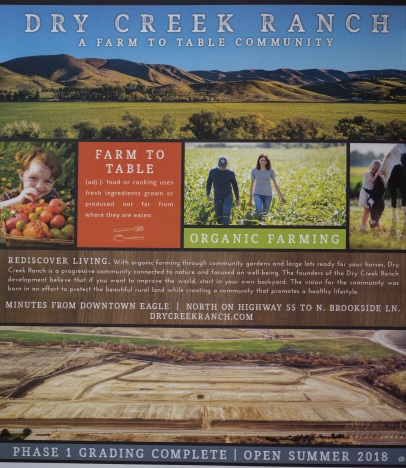

A few months ago, when I glanced at a full-page ad for an Ada County housing development that declared itself, in four-color glory, “A Farm to Table Community,” the hair on the back of my neck stood up. How does a spec development planning to replace excellent farmland with 1,800 or more homes earn the right to hitch its fortunes to a movement Edible Idaho has been documenting and championing for half a decade? Especially with an ad juxtaposing smiling children, fields of corn and baskets of tomatoes with an aerial photo of freshly graded ground, bereft of topsoil and labeled “Phase 1?” How is that not the opposite of what the local food movement stands for?

Well, after my heart rate slid back to normal, the journalist in me remembered that every story has multiple sides and this one likely did too. If nothing else, the Dry Creek Ranch development provided a reason to explore the much larger issue of ag land loss in Idaho—especially now that we’re the fastest-growing state in the nation—the Wall Street Journal estimates that Idaho could add another 200,000 people by 2025—and that growth will surely have a massive impact on food and farming here. So that’s why Edible Idaho is diving into the challenges facing ag land loss and, by extension, the future of local food.

Using Dry Creek as an example of recent tensions between developers and farmers, Edible Idaho contributor Carissa Wolf learns that Ada County could lose as much 240,000 acres of farmland to development by 2100, a trend that has already pushed small-scale farms like Peaceful Belly out of Ada County and others as far as eastern Oregon.

Writer Harrison Berry interviews an expert who helped write a Boise State University research study that predicts that “there will be solid urban development from well east of Boise all the way to Parma ...,” a statement that sounds eerily prescient after news that the Star City Council approved the annexation of 1,554 acres of farmland for a 3,000-home development in early May.

Our resident contrarian, Casey O’Leary, reminds us, though, that much of Idaho’s farmable land already lies fallow, not due directly to development, but through misguided agricultural policy, a cultural dislike of farm activities near urban areas and other problems.

Still, there is room for hope: Dan Meyer charts a way to work with developers that potentially provides financial rewards while preserving local farms. He cites a subdivision in Fort Collins, Colorado, as a possible model. And all across the United States, a 2016 Urban Land Institute study points to successful partnerships that bring real estate developers, farmers, restaurant owners, community organizers and urban planners together to build sustainable “agrihoods.”

So, don’t underestimate the power of motivated people to make positive change in the face of bad odds. To that end, Edible Idaho is trying something new: a section we’re calling “Local Voices,” a collection of short articles by Idahoans willing to weigh in on the issue of ag land loss. We asked developers, public officials and others on the pro-development side of the debate to join in too, but not a one took up our offer. I’ll let you draw your own conclusions.

Finally, it’s summer, and we’re the first to admit that wrestling with the issue of ag land loss is less appetizing than, say, publishing a magazine full of glistening grilling recipes. But with Idaho farmland at risk, isn’t it high time we asked ourselves how many more summers we’ll have of ultra-fresh corn and meat raised by ranchers we trust? After all, there’s no local food without local farmland.