Growing Future Farmers: School programs introduce students to a range of options

For many Treasure Valley school children, their first exposure to largescale agriculture is through the Kuna Ag Expo. Put on every two years at Kuna High School by the local chapter of the Future Farmers of America (FFA), the event gives up to 4,000 students the opportunity to pet baby goats, grow their own pumpkin seed, climb on tractors, eat locally produced ice cream and, in general, learn more about where their food comes from.

For some students, that lights the spark for them to become interested in learning more about agriculture. Others come to agriculture education because family, friends or neighbors are farmers, or they live in a rural community. Others just discover they like growing plants or raising animals. And as Idaho consumers become more interested in organic, non-GMO foods and other alternative farming methods Idaho’s agriculture education programs are following suit, giving students the opportunity to learn about these methods.

While the current curriculum may seem to favor topics some feel are more relevant to larger scale, conventional agriculture—production methods that use chemical fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides to manage crop yield and pests, as well as genetically modified organisms— that’s because students need to be prepared for common practices in industry, says Ariel Agenbroad, area extension educator in food systems and small farms for the University of Idaho Extension.

“A lot of secondary-school ag programs might seem heavy on the side of conventional ag, agribusiness and biotechnology, but these programs are training future professionals and they need to be prepared to enter that workforce,” she says—particularly students looking for local jobs after graduation.

But classes are starting to include alternatives, particularly when students, their families and the community request it, such as low till/no till, organics and production methods like hydroponics and aquaponics. And while schools in communities with more organic farms tend to have more instruction on organic farming, other schools teach at least basic organic farming as well.

About 70 Idaho school districts teach at least one class considered to be “agriculture,” ranging from Introduction to Agriculture Education to Agricultural Business and Economics, according to the Idaho State Board of Education. Curriculum guides are developed at the state level to meet academic standards, Agenbroad says, but individual instructors can choose which classes they teach, based on their capacity and priorities of their district and community, and they have a degree of flexibility in how they teach and what is emphasized in the curriculum. Standards are updated every five years.

At least 80% of state agriculture standards must be met to receive state funding, says Dr. Alison Touchstone, an agricultural education instructor in the Kuna Joint School District. Standards can be met in a variety of ways—including alternative methods. The other 20% can be up to the discretion of the local instructor and education district, allowing the program to address the interests and needs of the enrolled students and local community.

Every agricultural program has a Technical Advisory Committee of community representatives that influences curriculum taught in the classroom. Some include organic farmers which means local programs can include tours of organic dairies and work with organic community gardens.

Another path for Idaho agricultural education—which can start even before high school—is through extracurricular activities such as 4-H and the FFA. These give students additional opportunities to learn how to raise livestock and crops, as well as being mentored by caring adults, says James Lindstrom, 4-H youth development program director for the University of Idaho Extension in Moscow. “You can buy organic 4-H eggs in many communities,” he says.

One aspect of Idaho agricultural education is practical instruction, also known as Supervised Agricultural Experience (SAE), where students raise their own livestock or crops under the mentorship of another farmer, sometimes a family member. This can include organic production if students are interested.

“As kitchen gardens, urban agriculture and alternative production methods continue to expand,” Touchstone says, “more of these opportunities become available to students and teachers.”

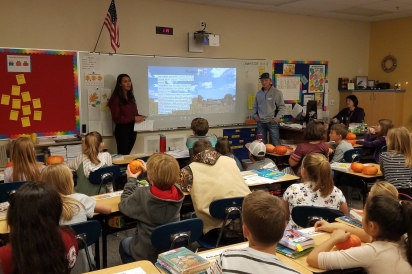

If a community wants Idaho agriculture teachers to include more information about organic and non-GMO livestock and crops in their classrooms, they should have students, parents and the community let them know they’re interested. In particular, farmers who use these methods can work with local schools and organizations such as 4-H and FFA to offer guest lectures, tours and mentorship opportunities. “There’s room for it all,” says 4-H director Lindstrom.