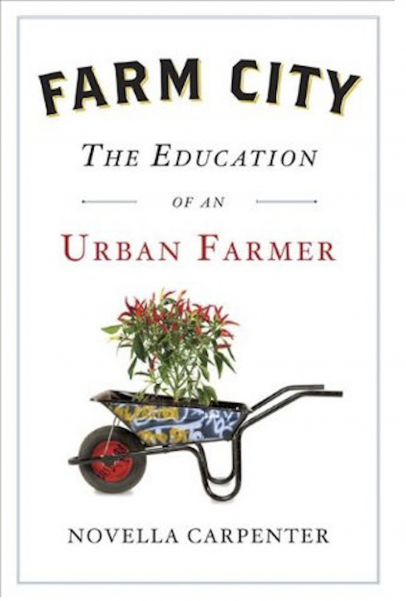

Farm City: The Education of an Urban Farmer by Novella Carpenter

When one thinks of a farm, usually it is a quaint image from sometime in the 1950s, with rolling hills of green, a large red barn, a rickety tractor. Or perhaps more modern-day, we imagine Instagram-filtered rows of gleaming vegetables and adorable pictures of baby animals. It is rare, however, to find someone who imagines these kind of romantic agrarian snapshots in a vacant lot in the heart of downtown Oakland, California. Novella Carpenter is that someone, creating not only a homestead but a sanctuary on a piece of “borrowed” land in the middle of an urban jungle.

Farm City is a memoir of her third year in Oakland, after moving into the neighborhood known as “GhostTown,” a reference to the many abandoned and decrepit houses. Next door to her apartment, she set up her homestead in a vacant lot, which she “repurposed” into a farm, complete with a garden, chickens, bees and more with the help of her boyfriend, Bill, and a variety of eccentric neighbors. The story is written in three parts based on her challenges: turkeys, rabbits and pigs.

Each portion includes its own victories and losses, including Carpenter’s butchering of Harold the Thanksgiving turkey, the discouraging loss of chickens to an opossum and dumpster-diving behind posh restaurants to feed the pigs.

GhostTown is the farthest you can get from an idyllic postcard-esque countryside. On one side is Lana, an eccentric neighbor with a speakeasy in a nearby abandoned warehouse. On the other is Bobby, living out of a broken-down car with extension cords snaking to his neighbor’s to power a TV and microwave. Gang activity, drug dealing and homelessness are all part of this Oakland neighborhood’s ecosystem. But Carpenter has a fondness for “down and out places,” as she describes them, and the urban chaos just adds to the charm. In the heart of it all, Carpenter sculpts a homestead that, while also as illegal as many of her neighbors’ lifestyles, begins to shape friendships and a sense of community in a neighborhood that appears to have had little of either.

Carpenter’s misadventures on her urban farm carry the humor of lessons learned the hard way, and are a reminder that whether its 100 acres of fields or 200 feet of weeds and broken glass, land is land. Farm City is a message to be read loud and clear: If you think you can’t farm where you live, think again.