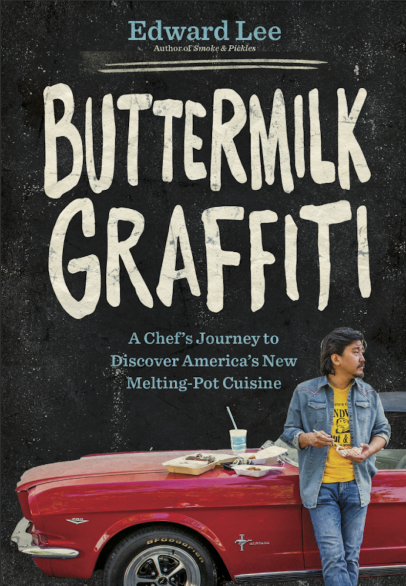

Edward Lee's Buttermilk Graffiti: A Chef ’s Journey to Discover America’s New Melting-Pot Cuisine

As the population of the Treasure Valley continues to grow, one positive consequence is an increasingly ethnically diverse population who have brought their culinary traditions to Idaho. For those who are adventurous and seek out new cuisines, Buttermilk Graffiti, a new book from Chef Edward Lee, is a must read.

He guides us on a journey across the United States to discover and celebrate the rich culinary and cultural diversity of contemporary America. In this combination memoir, cookbook and travelogue, Lee writes about cities and towns where immigrants have settled, thrived and now call home.

He leads us to places with long-established culinary traditions, such as Scandinavians in the Ballard neighborhood of Seattle and Germans in various parts of Wisconsin (unfortunately, Basques in Idaho failed to make his list), and also to cities and towns with more recent arrivals. For instance, did you know the largest population of Cambodians in the United States resides in Lowell, Massachusetts? The same goes for Peruvians in Paterson, New Jersey, and Nigerians in Houston, to name a few examples.

As a Korean American from New York City who runs restaurants in Louisville, Kentucky, and Washington, D.C., Lee is the perfect foil to explore how food triggers nostalgia for all new arrivals to the United States and to explain the adaptations “authentic” immigrant cuisines undergo as they eventually become much more than the sum of their parts.

He writes, “I always feel conflicted by the notion of authenticity. I am here in Paterson for some version of Peruvian food that is authentic, but what does that mean? In many ways, the food of immigrants is not authentic but frozen in time, reflecting the culinary moment when the wave of immigrants left their homes. This is the food of nostalgia. It gives an immigrant population a connection to its home country.”

Lee also tackles the notion of “cultural appropriation,” whereby chefs cook foods outside of their own ethnic heritage. “I’ve tried in this book to give a voice to the people who seldom get one. I’ve tried to investigate cultures I didn’t know a lot about. I’ve tried to cook food I was previously unfamiliar with. Maybe cooking the food of others is appropriation; maybe it is learning. Often I ended up with more confusion and more questions than answers.”

Despite this challenge, he offers up dozens of recipes inspired by the people he’s met and the food he’s tasted on his travels. Among the more unique are a Cambodian fish curry called amok trey from Lowell, Uyghur lagman soup from Brooklyn and a Nigerian spicy tomatobraised chicken with turmeric and cashews from Houston.

At the heart of this book is the essential question “What is American food?” Lee turns to Los Angeles Chef Ricardo Zarate, born and raised in Peru, for a possible answer. “When people ask me what is Peruvian food, I have the hardest time to explain. I say to them, ‘Peruvian food is a pot that has been simmering for five hundred years.’ The first ingredients were the Incas and the Spaniards. Then we added Africa and Morocco to the pot. Next is Italian, with a little German and French. Then a lot of Chinese. The last ingredient is Japanese. And the pot is still simmering.”

Lee says, “I love that description. It is a perfect metaphor. One day, I hope we can describe American cuisine in the same wideopen way.”