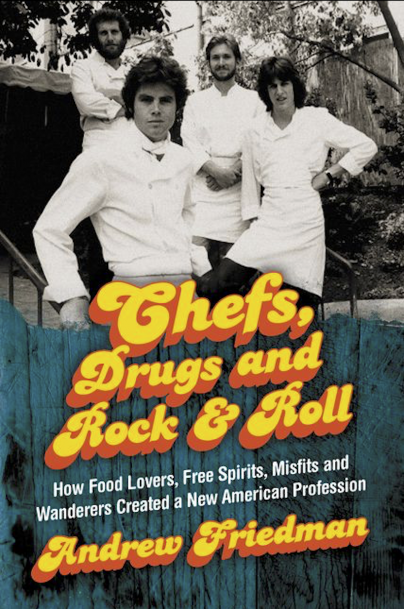

Andrew Friedman's Chefs, Drugs and Rock & Roll

While working as a kitchen intern in 1984, chef David Kinch got into the one fistfight he’s been in during his life. Kinch, who now owns and operates the three-Michelin-starred restaurant Manresa, was at a highend hotel in French Burgundy country. One night he found himself alone with the hotel’s pastry chef, the brother of the hotel’s sous chef, a pair that he referred to as “the definition of douches.” The pastry chef kept deriding him as Americain. Americain. Kinch snapped, pushed him against a wall and started hurling eggs, which just happened to be within arm’s reach.

“I was hitting him hard,” Kinch said. “I was throwing them like baseballs. He was cowering in the corner and I emptied the whole fucking tray on him, just one after the other, maybe 60 eggs as hard as I could from 15 feet away.”

Kinch stormed out, leaving the pastry chef to clean up the mess. When he returned to the kitchen the next day, Kinch fully expected to be fired. Instead, nothing happened. Moreover, the pastry chef did not speak a word to him. He had proven himself and rose past the unfounded stereotype that French chefs held about many American cooks.

The showdown illustrates the love-hate dynamic between a subset of young American cooks desperate for knowledge in the 1970s and ’80s and the French chefs who possessed and, in many cases, hoarded it. The tension between French and American chefs, between tradition and innovation, is central to Andrew Friedman’s book Chefs, Drugs and Rock & Roll.

Friedman doesn’t shy away from the debauched stories of that freewheeling era, but he also doesn’t wallow in them. Those stories are entertaining but can start to lose excitement when they are relied upon to carry the narrative. Instead, Friedman folds in social context to the story of these emerging cooks and burgeoning restaurants.

He tells the story of restaurants that now are institutions, whose chefs are featured on shows like “Chef’s Table” and “Mind of a Chef.” As history, it’s still fresh but it provides a worthwhile foundation to the glitz and glamour that now is associated with many chefs and restaurants in the limelight.

Kinch was part of a new breed of cooks who were emerging from an era of political and social upheaval. They were traveling the world, finding new flavors and applying a no-holds-barred attitude to cooking. They were rebelling against the stiffness and restraint so often found in the traditional fine-dining temples of France, which held sway over the culinary world for decades.

“There was a disturbance in ‘the Force’ about the Vietnam war and the uncertainty of ‘Hey, you might be shipped out and you can’t count on tomorrow,’” said chef Jimmy Schmidt, who trained in France and made his name redefining Midwestern cuisines. “I think that led to being more adventurous, a kind of anti-the-status-quo-type situation. Let’s go live it while you can live it.”

Like Schmidt, many chefs left the country in search of training in Europe’s revered kitchens. There also were hordes of young cooks who simply set out seeking adventure, and maybe a few new ingredients and flavors to add to their arsenal.

“You’re out there, you’re either traveling with a boyfriend or girlfriend or you’re single and you’re meeting kids from all over the world, and you’re having this sort of seminal experience that’s filled with sensuality,” said Los Angeles chef and radio host Evan Kleinman. “So, you’re experiencing your own sexuality. You’re drinking wine. You’re eating food that’s two steps from the field, in a totally joyous, non-Puritanical, nonjudgmental way. For a lot of us it’s the first time that we’ve ever experienced food in this context.”

When cooks traveled through Europe, they found a food that was rooted in fresh ingredients from nearby farms and foraged goods. They were able to source seemingly exotic ingredients with ease. And they were able to get these rarified items fresh. It was mind-blowing for young cooks who hadn’t experienced that kind of cooking and relationship to food. However, when they returned to the U.S., they found very little of that sourcing and appreciation of ingredients.

As a result, if cooks wanted new, fresh ingredients, they had to find them on their own. And they had to do so the old-fashioned way, without the aid of a search engine. For example, chef Larry Forgione was able to track down morels in the Pacific Northwest by way of mycological groups in the area. He found wild hickory nuts in Indiana and, eventually, American wild persimmons.

“I don’t think any of us were doing it to become famous; it just happened,” Forgione said. “We were doing things that we believed in, that we loved.”

With new ingredients at the ready, chefs were able to test the limits of their imaginations. They were breaking the rules and diners were responding. When Nancy Silverton took a job at Michael’s in Los Angeles, she was able to cook desserts that were described simply by their ingredients. She didn’t have to cook lava cake or tiramisu or any other preconceived dish. Cooks realized that they didn’t have to follow a certain path. They didn’t have to cook to a mold or to a certain cuisine. They felt free to experiment and test boundaries.

“We didn’t know what you’re not supposed to do,” said chef Jeremiah Tower.

With new ingredients in their arsenal, chefs then started to branch out and test what they could do with these new items. They were looking everywhere for inspiration and often just having to try things out.

“There were a lot of times when cooks on the line would say ‘Hey, Charlie, I was reading this article last night about morels. Do you think we can get some morels in?’” chef Gerry Hayden said, referring to Chef Charlie Palmer. “And the next thing you knew, morels showed up. It took chutzpah.”

While much of the cooking still was rooted in European techniques, American cooks were trying to make the food their own and adapt it to their own locations. And that search produced some innovative techniques that still regularly show up in fine-dining kitchens.

“Oil and cheese from the cheese and tomato,” Burke said, recounting the inspiration for flavored oils. “It was red. It looked pretty on the plate. I’m, like, ‘I can flavor oils, man!’ Then we started making them colorful. Curry, tomato. Now I’ve got a lighter sauce.”

The lessons gleaned from these American chefs are important ones today. They speak to cooks who are trying to adapt to whatever resources and personnel they can find. The cooks who laid the foundation for today’s restaurant landscape didn’t necessarily have a lot. Some of them were in the right place at the right time, but most made their names through hard work. They did the legwork to build supply networks. They broke rules and defied expectations. They created their own style.

In a time of food celebrities and overzealous media coverage of all things related to food, it’s refreshing to hear cooks and restaurant owners talk about pure, unadulterated passion for cooking and their drive to simply make the best food they could.

David Kinch | @davidkinch

Manresa | @manresarestaurant

Andrew Friedman | @toquelandandrew

Chefs, Drugs and Rock & Roll

Nancy Silverton | @nancysilverton

Jeremiah Tower | @tower.jeremiah

Chef Charlie Palmer | @chefcharliepalmer