Adaptation is the Name of the Game: Tracking agriculture in North Idaho through the years

When it comes to agriculture, Idaho has a split personality. Although agribusiness and the economic activity it generates represents 20% of the state’s overall economic output, according to a 2016 University of Idaho report, Idaho’s northern counties contributed less than 1% to the state’s agricultural economy. That should cause some to wonder what is grown upstate. Well, plenty—including population, which is one of many factors continuing to redefine farming in areas such as Kootenai County, where adaptation is the name of the game.

THE PANHANDLE’S AGRICULTURAL ROOTS

Regional farming began with the tribe, said Kootenai County historian Robert Singletary. By 1880, non-native farms in the county numbered about 20, growing legumes, wheat, oats and hay, yet as forest land was cleared and populations grew, farms increased rapidly, numbering 1,300 by 1930.

Commercial farming got a boost when Spokane-based railroad engineer D.C. Corbin and Washington Water Power teamed up to irrigate 6,000 acres of prairie from nearby Spokane River. With abundant water, orchards blossomed and growers were swept up in the turn-of-the-century craze for apples—until central Washington supplanted the Spokane region as the fruit capital.

That abundance of water, as it turns out, has been a double-edged sword.

“In order to be proficient like in the beef cattle industry, you have to have areas where you can graze animals,” noted James Church, University of Idaho Extension educator for commercial industries, whose specialties include beef cattle production, marketing and management. Neither the overall wetter climate nor colder winter weather of North Idaho are ideal for large-scale livestock operations, said Church.

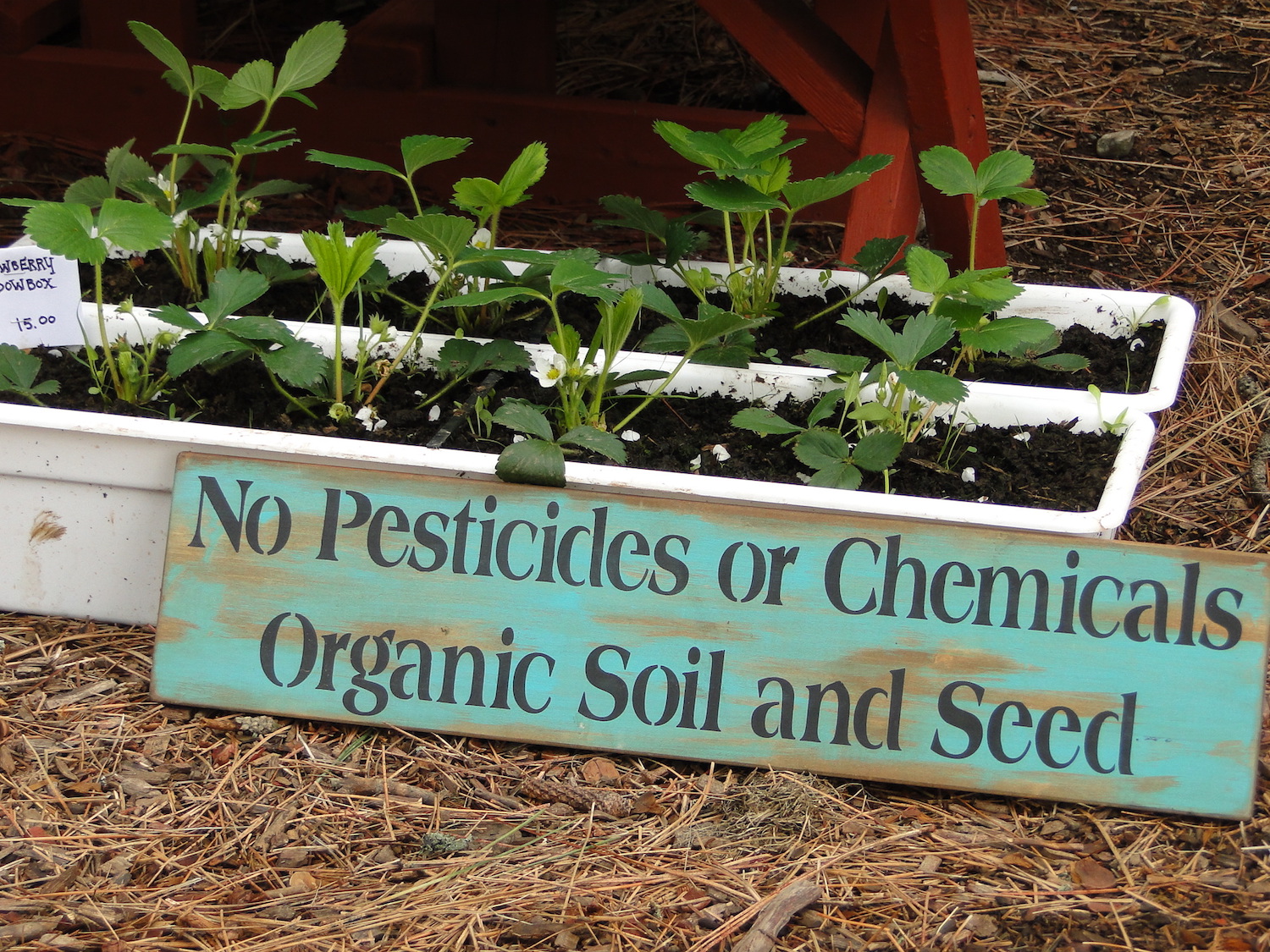

He is, however, seeing more targeted production, such as by Lazy JM Ranch, a boutique, artisan grass-fed/grass-finished cattle operation run by John and Betty Mobbs. Their niche-marketing approach touches on health consciousness and eating locally and affordably (they offer an installment plan). They also offer education, including hosting their customers for an afternoon of food, information and entertainment on the Lazy JM. “We do not use antibiotics, hormones or grain. We are not a conventional beef product. I have to ask many questions to make sure we are the right product for the right consumer,” said Betty.

CHANGING FACE OF THE PRAIRIE

Although large-scale livestock operations are unlikely to gain purchase in the area, the prairie was ideal for maintaining grasses, including wheat and Kentucky bluegrass planted for seed.

“Really, the only way you can farm up there is [with] a perennial crop,” said Bob Smathers, regional manager for Idaho Farm Bureau Federation based out of Moscow, Idaho.

Two factors coalesced to reduce the amount of both crops, especially bluegrass. Part of farmers’ long-standing process had been to burn the stubble, which for bluegrass prompted regrowth without costly replanting. That ran afoul of a physician-led Sandpoint-based group, Safe Air For Everyone, who held that the smoke caused respiratory problems for their patients. After years of costly litigation and uncertainty, the federal appeals court in 2007 upheld a ban on field burning.

Some wheat growers switched to other crops like peas or looked for other ways to clear stubble, while some bluegrass growers went south to Palouse and Camas prairie regions, said Smathers, a Lakeland High School class of ’76 graduate who remembers when field burning was the norm on the Rathdrum Prairie.

The influx of people may have been the stronger impetus in the decline of larger-scale farming as population continues to exceed state and national numbers. Recent headlines describe Kootenai County communities—the third-most-populous area in the state—bracing for growth. In Post Falls, for example, 2018 single-family residential permits surpassed totals from the two prior years, and that doesn’t include increased commercial development. History suggests the trend will not abate: From 1969 to 2017, the county’s population rose 350.3%.

GROWING WHERE YOU’RE PLANTED

Land tracts north of Coeur d’Alene tend to be larger, especially in Hayden and Dalton Gardens, whose name echoes the turn-of-the-century vision of homes surrounded by fruit trees. In amongst these and other neighborhoods, urban farming continues to expand with places like the Coeur d’Alene Co-op, whose specialty is heirloom plants and chickens; Ursa Minor Micro Farm, specializing in greens and eggs; and Bloomin Garden and Plante Family Farm, both providing CSAs.

If you get enough small farms, it can affect a food system, said Ellen Scriven, who runs a six-acre off-grid market garden with husband, Paul Smith, in Rose Lake called Killarney Farm. Certified organic since the state recognized the distinction in 1991, Killarney is revered for its experience and commitment to farming.

“A lot more can be grown through winter using season extension,” said Scriven, who is active in numerous organizations, including the Kootenai County Farmers Market, which Killarney has been with since its inception in 1986.

There needs to be more land for farmers, said Scriven—she envisions an incubator program—and increased education. “University of Idaho has really gotten going,” said Scriven, who has guest lectured at “Cultivating Success,” a statewide educational program for future farmers jointly produced by Washington State University, University of Idaho and Rural Roots, a 22-year-old Moscow-based advocacy group.

Another challenge? Restaurants, said Scriven, who recognizes that commercial and larger-scale requirements are different than retail, yet would like to see more chefs shopping at the market, which nonetheless continues to gain in popularity with consumers.

During one Saturday in 2018, Kootenai County market manager Beth Tysdal reported counting a steady 5,000 visitors. Vendors, which include a small percentage of nonfarming booths, self-reported half a million in sales last year. Attracting farmers is also a priority, including reduced-fee day passes for newcomers to try their hand at selling their wares, yet the market space itself is at capacity, said Tysdal, and they continue to cautiously evaluate expansion.

There are unique challenges faced by North Idaho’s agricultural community that southern Idaho, with its more hospitable agricultural climate and vast grazing lands, doesn’t face. But both share a common conundrum: people’s engrained approach to shopping and eating. “Most people aren’t geared for eating seasonally,” said Scriven. And that will continue to be a challenge for local-food communities everywhere in Idaho.

University of Idaho Extension

Lazy JM Ranch

Idaho Farm Bureau Federation | @idahofarmbureaufederation

Coeur d’Alene Co-op

Ursa Minor Micro Farm | @ursaminorcda

Bloomin Garden

Plante Family Farm | @plantefamilyfarm

Killarney Farm

Kootenai County Farmers Market | @kcfmidaho

Rural Roots