The Quest for the Lost Apples of the Palouse

This year, five apple varieties once believed to be lost were recovered in the historic orchards on the sloping hills of Steptoe Butte. David Benscoter has bitten into apples no one has tasted in 100 years. At his home in Chattaroy, Washington you can find him poring over county fair records of prize-winning fruits, thumbing through old orchard catalogs, and reading nursery flyers to guide his search for the lost apple varieties of Whitman County.

“When I retired, I didn’t have any interest in looking for lost apples. It was just something that jumped out and grabbed me one day when I was helping my neighbor,” Benscoter said.

Benscoter’s neighbor asked for help picking apples on her 100 year old farm in Northern Spokane County. He grabbed a ladder and a bucket, but returned from her orchard in just a few minutes: the apples were all too high and neglected to pick. Benscoter promised to return in late winter to prune the trees, and promised she would have buckets of apples in just a few years. He said thoughts of his neighbor’s orchard nagged him all winter.

“I knew that they weren’t going to be the kind of apples that I ate – no Honey Crisp or Golden Delicious,” Benscoter said. “So I started digging on the Internet and got completely fascinated by the whole history of apple growing in eastern Washington.”

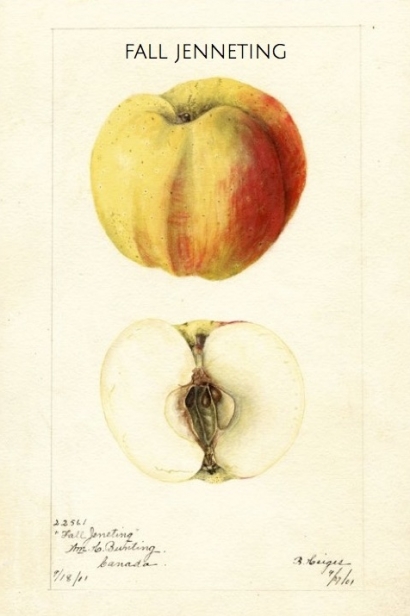

Benscoter’s investigative nature took hold. He was rewarded with finding an extremely rare Fall Jenneting apple in Colfax in 2013. Then, on the sloping hills of Steptoe Butte in 2014, he made what was to be the first in a long line of lost apple rediscoveries on the Palouse.

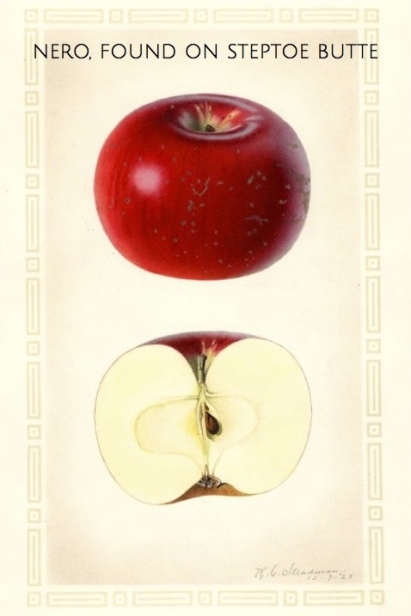

This first fruit, the previously-thought-extinct Nero, came from a 125-year-old apple tree, and was once grown all over the country. The orchard in which Benscoter found the apple originally belonged to Robert Edward Burns and his wife Mecie Hume.

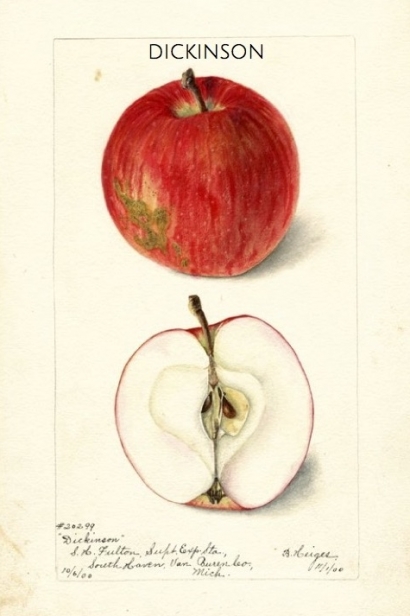

Benscoter’s modern discoveries could well be due to Burns’ dreams of managing an apple orchard. After enduring a failed crop of wheat in 1893, Burns family history shows that he decided to diversify by planting apple trees. Unfortunately, inexperience and inability to repay loans caused Burns to lose his farm in 1899. Despite the tragedy of losing his land, and luckily for the modern apple detective, Robert Burns had planted at least one Nero tree that survived. A McAffee and a Dickinson tree made it, too — all believed lost forever until Benscoter rediscovered them.

A Lost Heritage

“It is estimated that of the 17,000 named apple varieties originating in North America, only around 3,000 still exist today,” Benscoter told the Spokesman-Review in March of 2017. “Some of the lost varieties are truly extinct, having been chopped down for firewood or ripped out to make room for more profitable crops or buildings,” he said.

According to The New York Times, “about two-thirds of the $4 billion apple industry is now concentrated in Washington State — and 15 varieties, led by the Red Delicious, account for about 90 percent of the market.”

In Whitman and Latah County in the late 1800s and early 1900s, many homesteaders endeavored to supplement their living by planting fruit trees where they couldn’t plow other crops. By 1914, Historian John Fahey wrote that Whitman County had nearly 240,000 apple trees. Spokane and Stevens counties had nearly a million.

“The Palouse used to be the cradle for orchards,” Amit Dhingra, an associate professor of horticulture said in an article published by Washington State University. “When irrigation arrived in the Columbia basin, the Palouse industry was decimated, but the trees survived.”

The area is now ripe with abandoned and unkempt historic orchards. The lost varieties linger, their purplish branches and knobby trunks going undisturbed for months. In the midst of this agricultural silence, Benscoter continues to comb antique ephemera: newspapers, orchard flyers, and nursery catalogs from old farms on the Palouse.

“I have a list of apples that I know were growing in Whitman county, and that’s the list I was relying on,” Benscoter said, referring to his first discovery. “It was so new, and really, I didn’t know if I was looking for Bigfoot. Are we looking for something there was no chance of finding?”

Waiting To Be Found

Men and women across the world have taken it upon themselves to rediscover rare and thought-to-be-extinct heirloom varieties too. John “the Apple Whisperer” Bunker, hunts for his in Maine. Tom “the Appleman” Adams has been working from the Marcher Apple Network on the English/Welsh borderlands. This unique breed of private eye is alive and well.

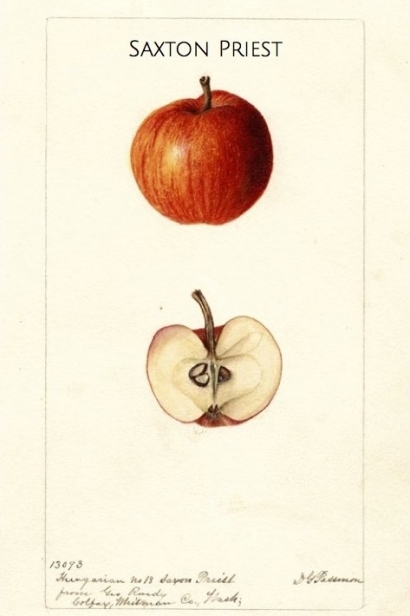

And they have tools, of course. Old books are a necessity. Apples have up to 50 different characteristics, and written descriptions alongside watercolor paintings from the USDA Pomological Collection — the majority of which were created between 1894 and 1916 — have helped Benscoter and other sleuths identify the varieties they have found.

“There are watercolors and really lengthy descriptions: everything from the seed size, to the seed shape, to how long the stem is,” Benscoter said, “They go incredibly in depth and do an incredible job. It looks just like the apple.”

Benscoter works alongside experts from Fedco Seeds in Maine and Temperate Orchard Conservancy in Oregon to identify the apples by comparing written descriptions and old watercolor paintings. A 9-member lost apple committee was organized by the Whitman County Historical Society when Benscoter approached them about forming a partnership. Today, that partnership is known as the Lost Apple Project, and it continues to support the search for and then the reintroduction of the lost varieties.

“I think a lot of people are drawn to these old varieties. No one has tasted them in 100 years. Most of the people that I talk to are senior citizens, and when I talk about these old varieties, they think back to their youth and their mother’s pies. People are really curious to see what these apples taste like.”

This project shows no signs of slowing. Five more lost apple varieties were discovered this fall on the rolling hills of the Palouse: the Shackleford, Saxton Priest, Ewalt, Kittageskee, and McAffe.

“Right now I’m looking for more than 20 lost varieties of apples. I 100% believe we’re going to find more, there’s no question,” Benscoter said.

Moving forward, researchers at Washington State University are trying to bring these apples back using cuttings from lost Palouse orchards. According to the Whitman County Historical Society, if these heritage fruits can be reproduced, they could add new choices for present-day growers.

“Our food habits are changing,” Dhingra said in an article published by WSU’s College of Agricultural, Human and Natural Resources Sciences. “Consumers are demanding more variety. These apples are a way to get variety and reclaim our heritage.”

It seems the public agrees, and wants to help: in the past two months, Benscoter has received leads of close to 1,000 trees – on top of the ones he hasn’t had time for in the last two years. If the apple detectives are able to continue the way they have in the past few years, Benscoter has no doubt they will find more.

“My biggest source of finding old trees is people calling me and letting me know where old orchards are…” Benscoter said. “We think these apples are lost and extinct, but they are really just waiting to be found.”

Steptoe Butte

Marcher Apple Network

USDA Pomological Collection

Fedco Seeds | @fedcoseeds

Temperate Orchard Conservancy

Whitman County Historical Society

Lost Apple Project

Washington State University

This article was originally printed in Moscow Food Co-op's magazine, Rooted.