Pan De Higo: A Perfect Match for Figgy Pudding

It smelled like Christmas: fragrant figs being mixed with holiday spices, nuts and sweet sherry.

Inside his parents’ kitchen, Sean Aucutt was up to his elbows in a mixing bowl filled with sticky batter, while his mom and dad, Mary K and Tom, heated up honey, uncorked sherry and retrieved handpicked grape leaves.

These combined efforts and ingredients would soon yield a festive family tradition: Pan de Higo. Literally translated it means “bread of figs,” but it’s more commonly known as Spanish Fig Cake.

“Mom doesn’t like figs, but Dad and I really like figs,” said Sean.

“I think they’re horrid,” added Mary K with a slightly scrunched face. “I don’t like those little seeds.”

This holiday tradition began about six years ago and is now a staple of the Aucutt’s holiday gift giving.

While they started by following a recipe, the Aucutts’ Pan de Higo has since taken on a life of its own, being annually amended to optimize flavor, mouthfeel and presentation.

“There are a great variety of recipes for Pan de Higo. Some people put chocolate in it,” said Mary K. “Traditionally it’s made with almonds, honey, figs, cinnamon, cloves and sesame seeds. This is a very traditional recipe.”

“I think we probably use more sherry than most people,” Sean interjected through a smile.

The raw mixture is nothing short of delicious: the deep flavor of macerated figs, the crunch of the nuts, the snap of the fig seeds and sesame seeds, the warmth of the spices. The family production began with 18 pounds of light and dark dried figs, de-stemmed and placed in a sweet sherry bath to leisurely soak for a week. Grape leaves picked in the neighborhood months earlier, then blanched and frozen, are set out to thaw.

In mid-December on assembly day, the chopped hazelnuts and almonds, along with the sesame seeds and sherry (and a little more sherry), were mixed with the figs. Sean said distribution of the ingredients is key, making sure each bite contains a little bit of everything.

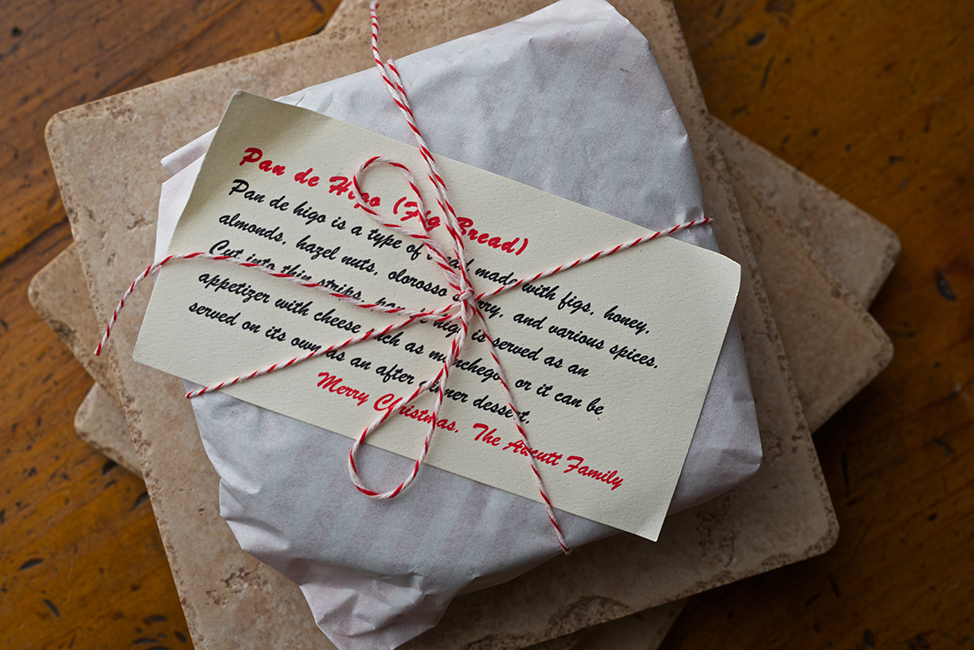

In the bottom of medium-sized ramekins, three large grape leaves were artfully overlapped. On top of that, Sean added a “large-snowball-sized” handful of the fig mixture and pressed it down. The leaves were then folded over what would become the bottom of the Pan de Higo and into a low-heat oven they went for half an hour. The grape leaves are purely for presentation: a natural gift-wrapping of sorts. By day’s end, dozens of beautiful little parcels lined the Aucutts’ kitchen counter ready for delivery to fortunate recipients.

“People are really pleased when they get this as a gift,” said Mary K.

“We give it with a slice of manchego cheese,” said Sean. “Usually it’s eaten for dessert, but it would make a great appetizer. I eat it anytime.”

While the Aucutts are of Basque descent and the accompanying manchego cheese also originated in the Basque Country (an autonomous part of northern Spain), Mary K was quick to point out that Pan de Higo is not Basque; it is of Spanish descent and, to Basques, there is a distinction.

“If you say it’s Basque, the [local] Basques will come and get us,” joked Mary K.

Traditionally the Spanish made Pan de Higo as a way to spice and preserve figs for the winter. The bread (or cake) lasts many months, even up to a year, according to Sean. By design, it also travels well. And (bonus) it scores pretty high on the nutrition scale with all those fiber-filled figs and protein-packed nuts.

You can find Pan de Higo on specialty store shelves and online, but the iterations seem endless. Some cakes are flat disks, some come as a roll that you slice, some look like fruity hockey pucks. The Aucutts’ version is yet another variation. I guess it’s like so many ethnic foods that span the decades and the continents: The basic principal remains the same, but the end products become highly nuanced.

Regardless of your preferred version—if you’re looking for an alternative to Grandma’s fruitcake this year (no offense, Grandma), trade in the candied fruit and brandy for figs and sherry.