Good Food Trumps Racism

Hearty lentils, teff flour and soft chunks of meat, vegetables and potatoes round out the menu at Kibrom’s Ethiopian & Eritrean Restaurant on Boise’s State Street. Between bites of injera bread, Berbere spices mingle with memories of Kibrom Milash’s childhood and swirl into stories of places and traditions connecting him to locales he’s called home and people he’s called friends.

Food offers much more than nourishment and a livelihood for Milash. Dishes that flow from his restaurant kitchen represent culture, friendship and community. His food carries symbolism.

“This food helps us—to have a lot of friends, to help our kids. This food is our life,” Milash said.

Last July, a vandal left Milash and his family a different kind of symbol: the n-word, etched in the paint of his wife’s car. If the vandal’s hate-filled message was intended to divide a community, isolate a family and harm a business, it backfired beautifully.

“I didn’t expect that in Boise,” Milash said of the racially motivated vandalism that stirred the community and shook his family, which fled conflict-torn Ethiopia as refugees.

Neither did Salam Bunyan, who just days earlier arrived at his Middle Eastern eatery, The Goodness Land in Boise’s Bench neighborhood, to find a swastika chalked on the concrete outside his front door.

“It made me sad. Not just because it scares me, but it made me sad because that’s in Boise,” Bunyan said. “Anywhere else in the world, that’s normal, but not in Boise.”

Sociologists have long noted that those who hold power often define what’s considered normal or abnormal. And across the country, surges of visible racism have become a new kind of normal.

The kind of racially motivated vandalism that scarred Bunyan and Milash’s property continues to swell across the country with spikes the Southern Poverty Law Center links to President Donald Trump’s rise to political power. According to the FBI, hate crimes against Muslims rose by 67% in 2015—the year Trump launched his campaign and bolstered his anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant political rhetoric. Hate crimes against blacks, Jews and LGBT people also spiked at the same time, according to the SPLC, which tracks hate groups and incidents.

But at Kibrom’s and The Goodness Land, the vandals didn’t win. The only surge Milash and Bunyan saw was a spike in business. In the days following the vandalism, patrons from far and wide showed with their stomachs and wallets that Boise and its region are too great for hate.

“The second day, I was having 100 people come in,” Bunyan said. “Many came from different cities.”

Milash also saw his customer base change. New patrons joined Kibrom’s mix of regulars and in the flow of familiar faces that come in and out of the restaurant, a steady stream of first-time patrons gather around large platters of injera and mounds of mellow spiced vegetables and lentils. And if they linger for a moment and ask about the food, they may learn about the symbolism and traditions behind the ingredients. They may learn that if they ordered #22, the shiro, they didn’t dine on just any chickpeas but on chickpeas reserved for honored guests according to tradition in Ethiopia; and the #15 dero wot isn’t just any chicken, but the chicken would-be brides must learn to prepare to show they’re ready for marriage. If you ask, the food speaks at Kibrom’s.

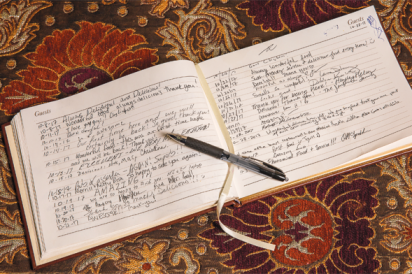

There are also messages from Kibrom’s guests. A notebook now sits on a dining table and brims with well wishes diners have left for Milash and his family in the wake of the vandalism.

“I’m going to keep that forever,” Milash said.

And Bunyan receives emails almost every day from people he’s never met. They send their support and love and Bunyan replies to them all.

“I am so lucky to have this kind of community. I couldn’t get this kind of community in my home country,” Milash said of the support he’s received. “I would just like to say thank you and keep supporting others.”

The kindness shown to The Goodness Land reminds Bunyan of the support he received when he arrived in Boise, a refugee from Iraq, after helping American forces track and apprehend Saddam Hussein. And they remind him of the help he received after both he and Milash lost their businesses in the 2016 International Market Fire. The arson left Bunyan with $200 in his pocket and nothing else.

“I told them, ‘Let’s start again … we’ll work hard,’” Bunyan said.

According to substantial research, refugees and immigrants do work hard. Over time, the National Academy of Sciences found that the average immigrant pays $80,000 more in taxes than they receive in benefits and one study found that immigrant businesses led a rebirth of Los Angeles neighborhoods that were riot torn in 1992.

Bunyan works six or seven days a week running the restaurant. “It’s not just to make money. I sell not just food—I show people the culture. I want people to feel like they traveled to another place,” he said. “Anyone who wants to come in is welcome.”