Roots of Our Family Tree

Perhaps you’re reading this in the morning, powering up with your regular morning brew of Coffea arabica or Camellia sinensis in your bathrobe made of Gossypium hirsutum, snuggled in your house framed with Pseudotsuga mentzeisii.

Or maybe it’s evening, you’ve popped an aspirin with a synthetic Salix alba to soothe your headache and you’re trying to unwind with your favorite beverage: a glass of Vitis vinifera or Hordeum vulgare flavored with Humulus lupulus, or, if it’s been a particularly tough day, something distilled from straight Zea mays. Even the fuel you used to drive home is derived from the decomposing bodies of plants.

The lives of humans are intimately intertwined with the plant world, and in some places the deep historical threads of that relationship weave together seamlessly with the present. Oaxaca, Mexico, is one such place. The likely birthplace of agriculture in the Americas boasts 10,000-year-old squash and 7,000-year-old corn seeds and to this day remains home to both the largest diversity of cultures (over 100 languages are still spoken) and the largest plant biodiversity in Mexico.

If you’re looking for a place to zoom out and marvel at humanity’s foundational relationship to plants, this is it.

I went to Oaxaca hoping to deepen my understanding of that relationship with regard to one specific plant: Zea mays, or corn. This quest led me, among other places, to the Jardín Etnobotánico (Ethnobotanical Garden) in Oaxaca City. The brainchild of celebrated artist Maestro Francisco Toledo and compadre Alejandro de Avila, the garden fills a two-acre courtyard in what was once a 16th-century monastery. Surrounded by massive stone walls in the shadow of the immense Church of Santo Domingo, it is a place that both nurtures and protects native Oaxacan plants—and also shares the stories of their complicated relationships to the often-messy enterprises of human civilization.

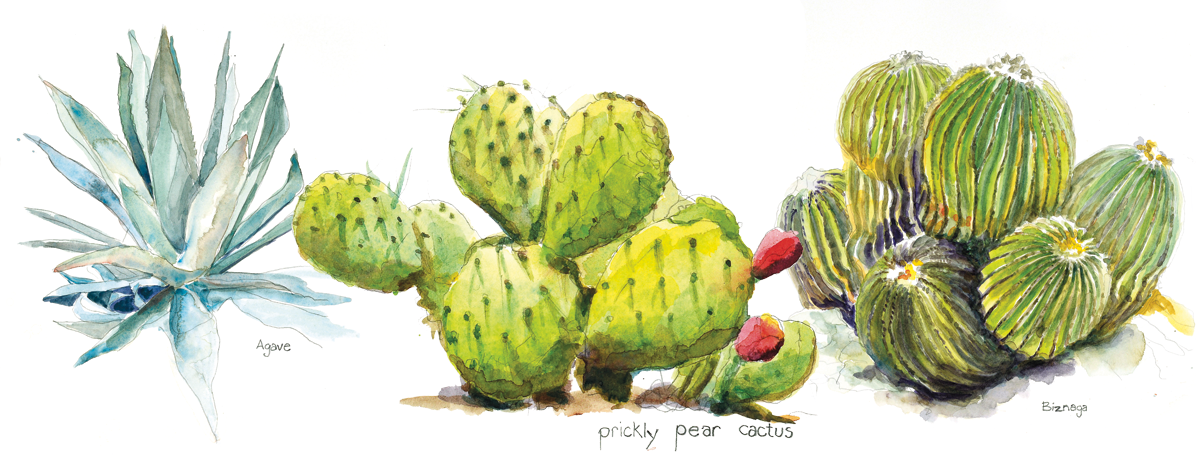

To start, you must have a guide to enter it, and the security guard at the entrance sees to that. The tour takes visitors through the heavy hitters among more than 900 species of plants—11% of the flora in the state of Oaxaca—in a series of distinct ecosystems, from the coastal communities sporting lush vines and epiphytes climbing the stately branches of ceibos and guanacastes to the desert ecosystems boasting enormous cacti and over 120 species of agave. But while the design of the gardens and the plants themselves feel exotic to my Idaho senses, the real inspiration for me lies in the human stories—the multitude of reasons these specimens have been and continue to be relevant to humanity.

Appropriately, the tour began in the “agriculture” garden. Our guide Georgina led us through the milpa, an intercropping system that utilizes three to 12 different species planted together to create more resilience in the field while satisfying human needs. From corn, beans and squash to amaranth and marigolds, she explained their uses as dye plants, pest deterrents and components of a nutritionally complete diet. She then talked about the history of domestication of maize, showing us a living teosinte plant. We turned the seeds from that grasslike ancestor of corn over in our palms, marveling at the complex stories of its transformation into heirloom corn—a central figure in the diet, creation story and spirituality of various indigenous groups over the past 10,000 years. She finished that section by talking about the real modern threat to the landrace corns of Oaxaca with the introduction of genetically engineered corn, and how the people of Oaxaca are locked in a battle to keep the GE corn out.

In every section of the garden we were introduced to a plant or group of plants, regaled with their historical and present significance and in many cases the modern threats to their continued survival. We picked Cochinil bugs off prickly pear cactuses and squashed them on our hands to make a deep red, carminic-acid-rich dye, which the Zapotecs still use to dye wool for weaving, and learned about how selling that miraculous little bug back to European cosmetics makers provided the money for the Spanish conquistadores to fund their colonizing armies and build the massive church that borders the garden. We gazed gape-jawed at the thousand-year-old, five-ton Biznaga cactus (Echinocactus platyacanthus) which had been rescued from the construction of the Pan-American highway and learned about how the species is threatened by overharvesting for a favorite Mexican candy. In the agave section, Georgina candidly shared that amateur mezcal makers are wiping out native agaves without realizing that only certain species are suited to making the famous Oaxacan liquor.

Around each bend awaited new botanical intrigues casting humans in intimate relationship with the plant kingdom while elevating guides like Georgina into the potent, Speak-Truth-To-Power role of interpreter. Through it all, I thought about Idaho, about our area’s own complicated relationship to plants, from Native foragers through Chinese gardeners, Mormon homesteaders, commodity monocultures, factory farms and so much more. After all, the lives of Idahoans are also intimately intertwined with the plant world. Sometimes it takes a trip to another country to remember that.