Bittersweet Memoir Offers Timeless Slice of Frontier Life

Frederick Jackson Turner’s 1890 claim that America no longer possessed a frontier would have surprised the people who settled in the early 20th century on newly available irrigation project land in south-central Idaho. Living conditions on the Minidoka and the Northside-Southside reclamation projects certainly looked a lot like “frontier”: unbroken soil covered with sagebrush and lava rock, isolated and rudimentary homes with no electricity or running water.

Women who came to the area found themselves facing intense physical demands in regard to basic housekeeping chores. Feeding their families demanded particular effort, as they milked cows and churned butter, canned and preserved food and ingeniously made do with substitutions (browned wheat for coffee, vinegar for lemon juice). Historians termed such culinary labors a crucial element to the survival of the frontier families, terming them “relentless,” even “heroic.”

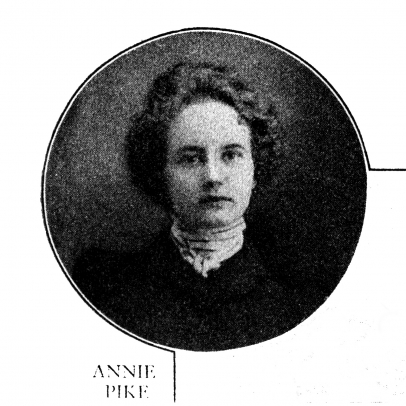

Among those women who settled on the new Idaho irrigation projects was Annie Pike Greenwood, whose lively and opinionated memoir We Sagebrush Folks has become a classic of Idaho literature.

Greenwood was an atypical pioneer, a cultivated woman with a college degree accustomed to a comfortable life. She came to Idaho after promotional literature seduced her husband, Charlie Greenwood, to give up his engineering career and claim an irrigated sagebrush tract north of the Milner Dam. Suddenly, Annie (“God’s little lamb,” she ruefully calls her naïve younger self, the woman who believed herself entitled to privilege) found herself a pioneer.

Food is a prominent theme in We Sagebrush Folks, and one that provides a vivid glimpse of just how hard those women worked. Along the way, Greenwood’s discussions of food beautifully encapsulate one of the memoir’s central themes: the narrator’s evolving sense of solidarity and identification (up to a point, anyway) with her neighbors.

Greenwood takes her first meal in Idaho en route to her new home with Charlie. The neighbor, Mrs. Curry, provides hospitality and serves food that strikes Greenwood as coarse and spare, including fried potatoes, boiled beans and fried sowbelly. “Conscious that [she] was sitting at the humblest table at which [she] had ever eaten,” Greenwood wonders at the “buttons” in the meat. Only much later, she wryly reports, did she realize “that my salt pork had been a mother.”

Greenwood comes from a family where servants cooked (the memoir’s first chapter recounts newlywed cooking disasters), but if she, her husband and their children who were born in quick succession are to survive, she must rise to the occasion, and so she does. She learns to fry rabbit, to make jelly out of stewed dried apples (from Mrs. Curry, whom she comes to admire).

She cares for 32 chickens, churns butter, engages in canning marathons (300 gallons of fruit one year, along with vegetables, pickles and jams), and bakes bread several times a week. She delights in tending a garden full of full of lettuce, onions and cabbages.

A milestone in her growing competence— and transformation—comes when she feeds 34 men at threshing time. She begins a day early, soaking a gallon of dried beans and pressure-cooking them, making many pies (“the men love pie, lots of pie, and all kinds of pie”), baking bread and cake, mixing salad dressing and chopping cabbage. Threshing day itself is an exhausting flurry of cooking and serving. “It was a big job, and I did it as well as any of the born farm women,” Greenwood boasts.

By the book’s halfway point Greenwood’s rhetoric lumps her among “we sagebrush farm women.” She constitutes herself as the group’s spokesperson, deploring frontier domestic abuse, praising her neighbors’ fortitude and skills, overtly advocating for political reforms to better their lives. When dainty and condescending “college cooks”—home economics extension agents sent by the government—arrive to teach the farm women to cook economically and correctly, she writes of them with disdain, though her initial attitudes were once like theirs.

So as Greenwood learns to cook she becomes a populist. But not entirely, for in her writing about food little hints of exceptionalism and amusement at her neighbors continue to appear. She’s arch about the men’s taste for plain food, for example, as she describes the harvest crew “wondering how on earth that garden stuff” [lettuce and herbs] got in one of the vegetable dishes.” She lets us know that she’s the only woman who covers with cheesecloth the milk jugs she cellars, decrying her neighbors’ unhygienic superstition that cream won’t rise if such a thing is done.

And despite her sympathy, she still can’t resist claiming some superior distinctions. “Folks! I can make strawberry ice cream like nobody’s business!” she proclaims. Prominently and repeatedly she boasts of her piemaking skills, noting that her raisin pie, in particular, was “famous, especially among the young people.”

Such competence and the family’s unremitting labor were ultimately no hedge against the railroad price-fixing, unscrupulous middlemen and canal companies and Depression- era economy. The family lost the farm to debt. Greenwood and her husband divorced. Living in a Salt Lake City apartment, she wrote commercial radio plays, along with fiction and poetry.

Though little of that latter work sold, it’s now accessible in the Special Collections Department of the Idaho State University library, thanks to a family donation. A preliminary scan of these materials suggests that Greenwood continued after she left the farm to use food in her writing to provide a mixed message about who she was. In her joyfully populist poem “Fried Silver Smelts,” Greenwood disdains epicurean delicacies in favor of those humble fish; “The Farmer’s Wife and Her Poem” laments that the poet cannot write because she “must light the fire, at once, for dinner for the men.” But the title of the collected manuscript of poems belies such folksiness, suggesting easy literacy of an uncommon level. It’s titled “For a Wreath of Parsley,” alluding to a line in American colonial poet Anne Bradstreet’s work in which Bradstreet herself self-consciously takes a womanly humble stand with a food metaphor, substituting a common herb for laurel in the wreath that the god of poetry, Apollo, wore.

We Sagebrush Folks, with its vivid tribute to “the great American beast of burden, the farm woman,” as Greenwood writes, stands as a sort of parsley wreath for its author, a modest triumph of craft. With its deft manipulation of food as a marker of identity, the memoir at once establishes the narrator as “one of us” literate readers even while opening the world of frontier women’s labors in a most convincing insider way. Even as we feel sympathy and perhaps a call to activism, she invites us to imagine that if we did find ourselves in such a situation we too might just succeed in producing an exemplary raisin pie.