The Idaho Pea Artist

Patient Work Breeds Big Results

Imagine a spring garden without Sugar Snap peas. If you were born before 1979, this shouldn’t be too hard, since they didn’t exist. Instead, farm kids would pick shelling peas and chew on the slightly sweet pods like gum before spitting out the fibrous mass and snagging another to make a canoe for floating down the irrigation ditch.

Dr. Calvin Lamborn was one such kid. Upon graduating from college, he was hired in 1968 by Bill Albers at Gallatin Valley Seed Company in Twin Falls. One of his early tasks as a plant breeder was to find a way to straighten the distorted pods of the snow peas his company was working on.

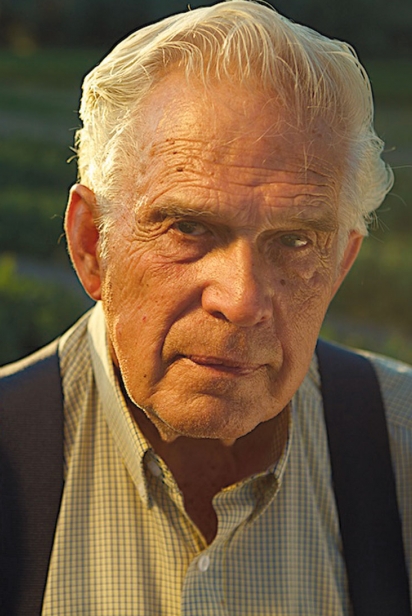

“I’d never seen snow peas,” the tall, kind-eyed, suspender-clad 80-year-old said. “I just knew shelling peas.”

But what he did have was a keen eye for observation, and he noticed a rogue shelling pea plant with flat pods and crossed it with a snow pea. Lamborn had no idea how much that cross would change his life. He shared one of the sweet, edible-podded progeny with Albers who, minus a few well-placed expletives, exclaimed, “This tastes like a fruit! Kids will love it!”

Thus Lamborn set out on a mission to stabilize that cross, and then increase the volume of seed. When he had enough true-to-type seed, the company released the Sugar Snap, which won an AAS (All-America Selections) award and gained Lamborn and Gallatin Valley notoriety. As the years went on, they released Sugar Ann, Sugar Bon and several other winning snap pea varieties, many of which were named after members of Lamborn’s family.

As goes the way with seed companies in the ever-globalizing marketplace, Gallatin Valley was bought out by Rogers Brothers Seeds, and then by Swiss-owned pharmaceutical company Sandoz, then Novartis and finally Syngenta, the world’s largest vegetable seed company. During the Sandoz era, Lamborn was downsized from the company, forced into early retirement in 1997 at age 63.

But Lamborn wasn’t done yet. He teamed up with long-time friend and former boss Bill Albers and has continued his breeding work in earnest since then. On four acres in Twin Falls, he’s been developing a host of mind-blowing new pea varieties that, thanks to the efforts of his son Rob, are finding their way into the kitchens and plates of some of the country’s most elite restaurants. New York City’s now closed wd~50 served Lamborn’s dark purple snaps in its steak béarnaise, while The Breslin infuses his oversized, super-sweet B-52s in vodka. In California, The French Laundry, Saison and Single Thread are also creating memorable meals with Lamborn’s new peas.

“You can meet anybody in the food world if you’re his son,” Rob laughed. “All I have to do is say ‘My dad created the Sugar Ann pea.’”

It’s thrilling for Calvin Lamborn to see the chefs excited. “What they want,” he said, “is the whole plant, to dress it down like you would an animal.” They can take the tough, old leaves and see the potential in them to create a delicious stock. The leaves of the pea plant are like stacking dolls, and each individual set, nestled inside another, reveals new possibilities to the innovative chefs who work with them. He has even bred a dainty-leaved variety that resembles curly parsley or chervil more than a pea plant, and chefs can’t get enough of it.

Like the artistry chefs display on the plate, Lamborn performs artistry in the field. He prides himself on putting his “signature” on every variety he breeds. Something unique but recognizable—his “spotted cow,” as he calls it, in reference to the Bible story of Jacob. In addition to the obvious color, texture and disease resistance, his varieties all have leaves and pods that are shiny, not dull. They’re distinctive.

“I don’t say it in a boasting way,” he clarified. “There’s art in everything that people do. Some people just see more than others. The world of genetics is an unseen world. You feel your way through by observing. It becomes an art more than a science. This looks better, this has some advantage.”

“I don’t take a lot of notes, but I make a lot of footprints,” he said with a smile. “I just keep coming back to the best, and crossing the best with the best until I get what I want.” (As to the practice of genetic engineering, Lamborn simply said, “I just don’t need it.”) “All of my varieties that are popular, I can take you to the field, to within 100 feet of where they first caught our attention.”

All of his footprints and time-consuming, old-fashioned plant breeding might suggest a leisurely pace. But Dr. Calvin Lamborn is in a race with some of the largest corporations on earth. The one who gets to the finish line first with a novel variety gets to patent his creation, effectively controlling all production and reproduction of the crop for the next 20 years.

It wasn’t always that way. Without the work of countless unpaid and unpatented small and large-scale seed savers throughout the thousands of years of human agriculture, we wouldn’t have the foods we have today. But, without ownership of their work, modern plant breeders can’t keep doing what they do. It takes at least seven generations to stabilize a cross, and that’s after countless crosses to get the magic combination in the first place. Lamborn estimates he’s done over 1,500 cross-combinations in his long career. Until the Plant Variety Protection Act of 1970 came into law (in part thanks to the lobbying of Bill Albers) allowing the patenting of novel varieties, a company like Gallatin Valley could have spent thousands of dollars on breeding and marketing a new variety, only to have another seed company that didn’t have all that cost invested in it simply buy the seed and, within a few years, grow out enough seed stock to outcompete the company that initially introduced it. “Pirates,” Albers used to call them. Unable to compete, Gallatin Valley Seed Company went the way of thousands of other small seed companies: bought out by ever-larger multinational corporations. Despite the unsettling ramifications of patenting living tissue, the Plant Variety Protection Act gave breeders like Lamborn the incentive to keep going.

When Lamborn was laid off, the ability to patent his work, combined with Bill Albers’ business savvy and camaraderie, kept him going.

“No researcher has a budget,” Albers grumbled. But he knew that if Dr. Lamborn bred novel varieties, he could have the exclusive rights for his fresh market pea business, and it would pay off eventually. Albers essentially created the market for the Sugar Snap pea in grocery stores, first in the produce section and later in the frozen foods aisle. While president of Gallatin Valley Seed Company in the late 1970s, he struck a deal with Albertsons’ vice-president of produce and liquor to set out a 1,000-pound pallet of these new fresh snap peas in his zone of stores, and the rest is history. Now you can’t even find one of those plastic pre-made vegetable trays without Sugar Snap peas on it.

So how special are Lamborn’s new peas? Their startling colors, from deep maroon to bright yellow tie-dyed with red streaks, certainly stand out. He envisions a new generation of vegetable trays that include several colors of snap peas, and he has his eye on these large markets as well as the small, high-end restaurant niches.

“These restaurants are exciting, but they’re not profit centers,” he acknowledged. “We couldn’t do that if we weren’t making money. They’ll buy maybe 100 pounds, but we’re interested in someone that uses 200,000 pounds.”

Thus, Lamborn also has an eye on breeding for everything from increased disease resistance to higher yields and smaller pods for largescale processors to ease of picking for field workers.

“I’m looking right now at a picture of an African woman with a baby on her back, bending over in a field to pick snap peas,” Lamborn said. “I want to breed something that makes it so she and other pickers don’t have to bend over.”

It’s startling to glimpse how truly huge Lamborn’s reach is.

“Pretty much every snap pea grown in any quantity around the world is one of my varieties,” he said. Mike Watkins of the huge Seneca Foods Corporation agreed. “Even Dr. Lamborn’s obsolete varieties are better than the competition.”

Albers’ long relationships with processors connect them with folks who can purchase in large quantities. Add in Rob’s connections with cutting edge restaurants and you’ve got the perfect pea-breeding team.

At age 80, Lamborn doesn’t plan on slowing down anytime soon. All but the youngest of his 21 grandkids have helped him in his fields. “I call it ‘Learn to Work by Weeding,’” he laughed. “Only Sophie hasn’t helped.”

“She’s 4, Dad!” Rob admonished.

“Julie was 4 when she started,” Lamborn retorts with a twinkle in his eye. “When they’re old enough, I pay them $10 per hour, and while they’re weeding, I give them $1 for each off-type they [find]. It sharpens their eyes. And a big bonus if they find a treasure in the field, something really unique.”

With all the buzz surrounding his newest releases, Lamborn never loses sight of the bigger picture. “There’s no end to what I want to accomplish. Each year I look at what we’ve got, I make all the crosses I can think of, and before I’m through, I’m thinking of the next round of crosses I’ll make.”

If that sounds tiring, consider this sage perspective from Lamborn, someone who loves his work as much as a person could: “Life is good if you’re involved with a good project.”

Casey O’Leary runs Earthly Delights Farm, an urban CSA and seed farm in Boise, and manages the Snake River Seed Cooperative, working with regional farmers to create a resilient regional seedshed.