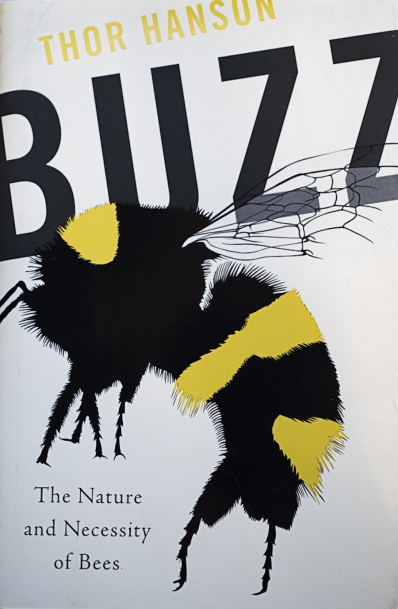

BUZZ: The Nature and Necessity of Bees

One hundred and thirty million years ago, dinosaurs weren’t the only animal intrigue afoot. Amid the lush jungle of green leaves and inconspicuous, wind-pollinated flowers, an insect-eating sphecid wasp started eating pollen. The earth would never be the same again.

Hunting insect prey that can fly or crawl away, or potentially kill you in the process of defending itself, is a great deal harder than sauntering up to a stationary flower and gorging yourself on protein-rich, conveniently helpless pollen. So the transformation from sleek, carnivorous wasp to fuzzy, vegetarian bee made perfect evolutionary sense. And in the magical dance of co-evolution, plants started making bigger, showier flowers and provisioning them with big sugar-rush caches of nectar to reward these new helpers for inadvertently transporting pollen on their bristly bodies from flower to flower while they feasted.

A far cry from the green (or at least visually flowerless) past, the flowery angiosperms have come to dominate our landscapes, our food systems, and even our very definition of beauty. In fact, in his book, BUZZ: The Nature and Necessity of Bees, biologist Thor Hanson interviews a handful of forward-thinking anthropologists with a stunning hypothesis: that we might never have become the big-brained humans we are today without bees.

As plants started producing more nectar, bees starting making and hoarding honey from that nectar. As an “obligate glucose consumer,” the human brain needs a massive input of calories to function— up to 20% of our daily caloric intake goes to feeding our brains—and honey is the food with the highest amount of naturally occurring glucose in the human diet. These anthropologists are studying both past and present hunter gatherer populations and finding evidence that honey, as well as pollen and bee larvae, likely accounted for a large percentage of our humanoi ancestors’ diets, which would have helped their brains develop as well!

This journey is merely one of many Hanson and a lively cast of characters lead the reader on as he explores the world of the humble bee, of which there are thousands of species with different nesting habitats, social structures, foraging habits and tongue lengths for reaching nectar in variously shaped flowers.

At the close of the book, the reader is left with a keen understanding of how crucial bees are to human survival, and how human activity threatens their existence and, by proxy, our own. As Hanson says, “Nobody trusts an exoskeleton.” Most human encounters with insects, especially flying ones that can potentially sting, end in swatting, screaming or poisoning. BUZZ offers readers an opportunity to get up close with these remarkable and vital earthly cohabitants, to marvel at their fascinating lives and perhaps even fall in love.