The Art of the Slaughter

Taking a clear-eyed look at what it means to turn life into food

Eileen Staichowski is having trouble choosing an outfit this morning. Two years ago, she quit a high-paying job as a safety engineer on the East Coast and moved west to turn her lifelong passion for food into a livelihood. She worked as a cheesemaker in Driggs, then took a job at the Idaho Hunger Relief Task Force in Boise, but still she felt the need to “fill the gaps” in her knowledge of farming and food production.

That’s why today she’s reflecting on which of her clothes are best suited for bloodstains.

After careful consideration she chooses a green flannel shirt and brown canvas pants: earth-tones and heavy materials to fit the crisp December morning. She then eats a quick breakfast and is ready to go; but before leaving her house, her boyfriend tells her to “have fun.” The two exchange a look acknowledging the awkward phrasing. Eileen is participating in her first livestock harvest—a slaughter of lambs—and “fun” isn’t exactly what she has in mind. A hug follows, and Eileen walks out the front door.

The slaughter takes place at Purple Sage Farms outside Middleton, about 25 miles from Eileen’s North End Boise apartment. The owners’ sons, Kelby and Mike Sommer, introduce themselves to Eileen with a hearty handshake. They will be Eileen’s guides through the process, and are happy to pass their knowledge on to this willing initiate. Eileen stands by a wood fence as the brothers guide a flock of 100 lambs to the corral. One 80-pound lamb on this farm will produce about 15 pounds of boned meat. Because the lambs are grass-fed, they’re much smaller than corn- and silage-fed lambs raised on feedlots, but their flesh is decidedly more tender and better tasting. Two sheep dogs nip at the lambs’ ears as the brothers shepherd the flock into a corral, where they cull the larger lambs from the smaller ones and direct the weightier creatures into a barn. Eileen follows them in and ask the brothers how they will select the animals for slaughter.

“Not much of a science to it. Whichever look the biggest,” says Kelby.

The brothers isolate a large, light-colored sheep and carry it out of the barn by its legs. The lamb is placed belly-up in a cradle-buck—a sawhorse-shaped device with legs that extend beyond their vertices to create cradling Xs that keep the lamb calm and positioned for easier bloodletting. Eileen watches from a short distance as Mike holds the creature’s legs and Kelby slides a blade across the animal’s throat, opening a wound that severs the creature’s esophagus, carotid artery and jugular vein. The lamb emits a gurgling sound as it strains for a final breath, and Eileen whimpers softly as two streams of blood flow into a shallow hole, dug earlier that morning. The blood forms a bright crimson pool in the morning sun.

Two minutes after the initial cut is made, the red flow turns to a trickle and the lifeless body is placed on a pallet. Knives are cleaned and sharpened, and the process begins again. The brothers invite Eileen into the barn to select the second lamb, and ask if she’d like to help carry it to the cradle-buck. Eileen doesn’t hesitate. The brothers make their de cision. Eileen grips the chosen lamb by fore- and hind-leg opposite Mike and lifts. She’s amazed by the lamb’s malleability, how easily it submits to this handling. She keeps hold of the animal’s legs after placing it in the cradle-buck and watches Kelby make the cut, gauging the tension of the knife against the lamb’s skin, measuring her resolve to do the deed herself.

A third lamb is selected and slaughtered, and then Kelby asks Eileen if she’d like to cut the fourth lamb’s throat.

“No,” she says. “I don’t have the technique.”

She’s worried about doing something wrong, causing the animal unnecessary pain or damaging the final product. Ultimately, it’s the tension that bothers her: the tension of blade on skin, the knife as intermediary between wills and bodies. How much tension is enough? How much is too little? Either direction has its risks, and she won’t be comfortable until she understands the space in the center.

So she has no problem stepping back, having learned from her work as a safety engineer that uncertainty often causes more damage than false confidence, and the consequences of a mistake here will be visceral—experienced as her own emotional pain by way of the animal’s suffering. Perhaps when she’s more comfortable with the feel of the animal’s body she will be comfortable inflicting the lethal trauma, but for now she’s content with her role as participant-witness.

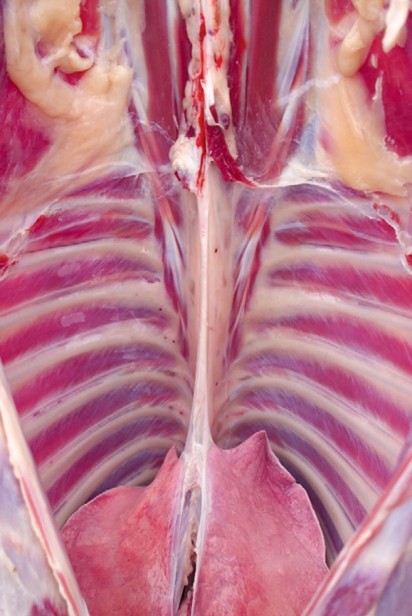

When the fifth lamb is killed and all the heads and hooves are removed with a reciprocating saw, Eileen picks up a knife and helps with the skinning. The brothers show her the way to slice the skin around the tendons near the animal’s knee and peel the subcutaneous fat layer from the muscle. Though Eileen’s first cuts are timid, she quickly gains a feel for the animal’s tissue, and soon the knife seems to create its own course between body and skin. “This is amazing,” she says a little later, her knife cutting an artery around the beast’s heart, “the way everything wants to come apart.”

The last separations are made on the carcass, and Eileen is taught how to cut the tongues out of the animals’ heads. With no clear demarcations of the shift, a process that began as life-becoming-death has become the body-becoming-food. Where did this change take place? Or was it always the same thing? Best not to think about it while holding a knife, though, says Eileen. This work requires concentration, and she can sort through those questions later.

The tongues are placed in steel pans with edible parts like the hearts and livers, and the heads are tossed with the rest of the offal in the wheelbarrow. Intestines are cleaned with metal rod-and-wire tools for sausage casing, and the lambs’ flesh and bones are hung in the garage, where they will age for a week or two, and then be further separated into edible parts: shanks for roasting, chops for grilling, the legs and shoulders ground for sausage. The parts will then be stored in freezers and either traded to other food producers or cooked in the homes of the farmers’ friends and family members.

The deed, it seems, is done. The brothers cart the unusable remnants of the lambs to a far corner of the pasture and bury them in a shallow grave. Years later, the descendants of the lambs killed today will feed on grass containing their nutrients: classic circle-of-life business. In the meantime, Eileen cleans her knife and washes her hands. She can’t say how much time has passed since breakfast, but she knows she’s hungry.