Spring Wheat by the Acre: Mathieu Choux of Gaston’s Bakery has a local vision for Idaho breads

After tying the strings on his baker’s smock, Mathieu Choux, owner of Gaston’s Bakery in Boise, produced two bags of flour and poured their contents into bowls on the worktable in the center of the baking floor. On his left, the bowl filled with white powder. Into the bowl on the right he poured flour that was almost khaki in color. Pinching some between his thumb and forefinger, he gave each a taste in turn.

“For the longest time, nobody thought of the quality of the flour for taste,” Choux said. “A good miller, for the last 50 years, was the miller who could make the whitest flour possible. All of that is changing.”

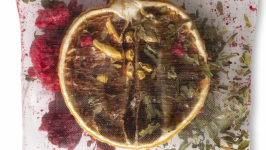

The white flour came from the 200-pound bags of General Mills Harvest King—the baking flour he uses in everything from baguettes to commercial-grade hamburger buns. The khaki-colored flour, however, was an orange-red spring wheat that came from Thresher Wheat in eastern Idaho, which Choux milled himself using the Unifine impact-milling system he built on the other side of the bakery.

To the untrained eye, the difference between the two flours is that between white and khaki, but for bakers like Choux it’s night and day.

White flour is produced when the milling process strips away the bran and germ from the wheat, leaving only the endosperm. Milled whole-wheat flour retains all three elements, preserving the vitamins, minerals, dietary fiber and protein that occur naturally in wheat. Choux said he hopes sourcing his wheat in-state and processing it himself will give his customers more nutritious bread products that have more than a little taste of home.

“I think it would be super cool if, over the years, we can have people recognize the different varieties of wheat, like grapes, like wine,” he said.

Normally, a baker looking to buy wheat to mill in-house would order it by the bushel, but Choux has approached a handful of Idaho wheat farmers with an unorthodox proposal: to buy their wheat by the acre.

“I want specific kinds of wheat, and sometimes you just have to put your money where your mouth is, and I want to be the one taking the risk,” Choux said. “The idea is to say, ‘OK, how much do you want per acre? I’d like to contract five, 10, 20 acres with you, and tell me a price that makes sense for you to do it.’”

One of those farmers is Brennan Henry Allsworth of Winnower Farm and Ferments in the Dry Creek Valley. Allsworth and Choux have arranged for Winnower Farm and Ferments to grow 10 acres of spring wheat for Gaston’s Bakery on his land. At 90–100 bushels of wheat per acre, that could net Gaston’s upwards of 1,000 bushels of wheat when Allsworth harvests it in August.

A member of the Snake River Seed Cooperative, Winnower Farm and Ferments also grows seed and heirloom corns, cabbage, cucumbers, eggplants, peppers and more that he sells at the Boise Farmers Market.

Allsworth said local wheat sold directly to bakers “closes a circle” of food production.

“I think it’s the next step for really helping with a thriving local, regional food system,” he said. “As we progress and try to get more of our year-round food from ourselves, I think grain is one of the next steps to be taken.”

Farther afield, but growing at a greater scale, is Jamon Frostenson of Frostenson Farms near Fairfield. When Edible Idaho spoke with him, Frostenson was still in talks with Choux about a possible deal and has 350–500 acres available. Choux said he is interested in purchasing 500–1,000 bushels of spring wheat.

Frostenson Farms is a dryland farming operation and relies heavily on spring rains to water crops and warm weather to ward against late frosts. Despite his commitment to selling locally, Frostenson said there are concerns that make supplying smaller buyers tricky: Farmers like him will “have to touch it and handle it a bit more. There are logistical headaches.” Nevertheless, he said, “Our vision of the future is, we want to see [wheat for Gaston’s flour] grown locally. The economics are irrelevant; we’re going to make it happen no matter what.”

With flour made with Thresher Wheat, Gaston’s has already begun to sell breads made with in-house-milled flour to the Boise Co-op, and sell house-milled pastry flour at its bakery. Choux said he doesn’t yet know how much of his bread will ultimately be baked with Idaho flour, and the full rollout of his experiment is expected to take place in the summer of 2019, when his partner farms harvest their wheat. For the time being, his objective is simple: “I want the cleanest bread I can bake,” he said.

Gaston’s Bakery | @gastonsbakery

Thresher Wheat

Snake River Seed Cooperative | @snakeriverseedcoop

Boise Farmers Market | @boisefarmersmarket

Boise Co-op | @boisecoop