This Thing We Do: 44th Street Winery

A neat row of galoshes—ranging from moss green to black matte to hot pink plaid—hide under a bench in the corner of the 44th Street Wineries tasting room. It’s easy to overlook them in this giant Garden City warehouse space, with light filtering in through frosted glass rollup doors, wine-barrel tables dotting the sprawling concrete floor and dozens of wine glasses hung upside-down on wooden shelves. But those boots are a great metaphor for what’s going on behind the scenes.

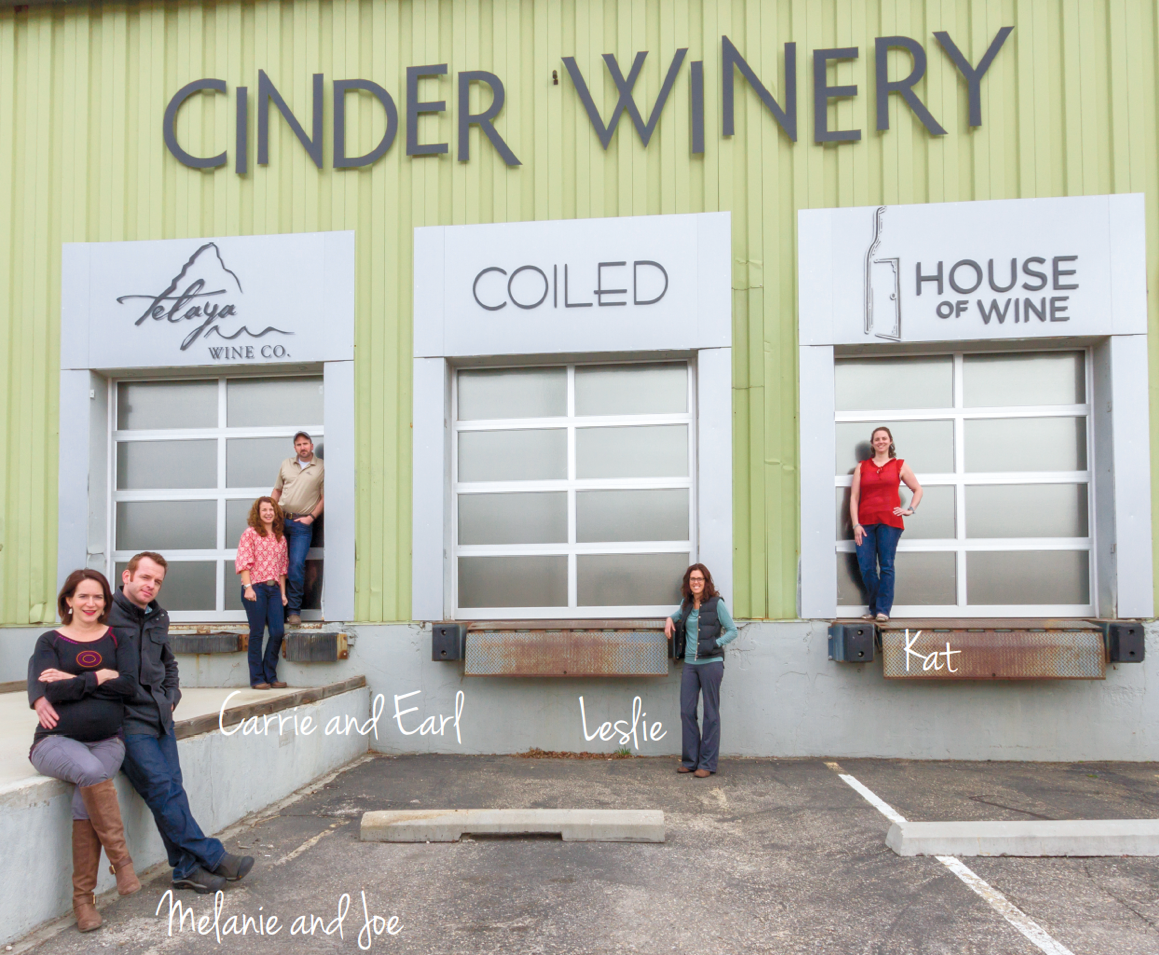

The 44th Street Wineries warehouse unites three urban wineries under one roof: Cinder, Telaya and Coiled. The building is also home to House of Wine, formerly Wine Wise LLC, a company that offers wine consultation, testing and educational classes.

“Winemaking and wine production, in general, is very capital intensive and so it’s a big barrier for a lot of small businesses to be able to start up unless you’re independently wealthy, which very few of us are,” said Kat House, owner of House of Wine.

So these four companies—and their rainbow array of galoshes—joined forces to share equipment, office space, a nursery and, on some occasions, advice.

“Technically, how it works is that Cinder leases the whole building and owns the majority of the equipment—like 95 percent of the equipment or something—and so we sublease to Telaya and Coiled and they contract out our equipment and labor,” explained Melanie Krause, winemaker at Cinder. “So there’s no interconnection between any of the decision-making processes—they’re totally unique wines, and unique wineries—they just essentially can come in and use the equipment and use the crew.”

It might seem odd, with winemaking being such a seasonal industry, that these companies choose to share resources during the chaotic peak of harvest. But, according to Krause, it’s actually more efficient.

“What happens in winemaking is about 70 percent of it is cleaning— before and after the process—and 30 percent of it is doing whatever we’re doing to the grapes,” said Krause. “So if we can save time on that huge amount of cleaning and sanitation by running the two sets of grapes through the machine, one after the other, it’s so much more efficient. It’s counterintuitive but it actually works well to have multiple wineries doing the same process on the same day, if we can line it up.”

But there are also some downsides to sharing a winemaking space.

“There’s always drawbacks to being in an environment where it’s not your house. It’s kind of like being a houseguest; you have to be respectful of the house that you’re in,” said Earl Sullivan, winemaker at Telaya.

So before any roommate issues could arise, the wineries sat down and agreed upon a set of cleanliness standards to keep everyone happy.

“We all have a cleaning protocol that we’re all really comfortable with,” said Krause. “It’s very rigorous so that every tank and all the lines and everything we’re using, when we switch companies, it’s all very, very well cleaned so we’re not getting a lot of cross-contamination of wine or yeast or anything like that between the companies. And that’s just one of the necessities of making sure that everybody’s happy working with multiple wineries in one space.”

Incubator-style arrangements like this are nothing new in cities outside of Boise. The Southeast Wine Collective in Portland, Ore., is home to five urban wineries and a tasting bar that offers supper socials and movie nights. By sharing a space, these winemakers are able to save money on equipment and disperse the costs of leasing a large building in an urban center.

In fact, according to an article by Tim Patterson of Wines & Vines, starting an urban winery can be 20-30 times less expensive than opening a traditional, countryside winery with an attached vineyard.

“Buying and developing 20 acres of vineyard land, enough for 3,000-4,000 cases of wine, at $50,000-$75,000 per acre—if you could find it at that price—and $30,000 per acre for land preparation, irrigation and trellis, means starting with $1.5 to $2 million in expenditures before a single grape is picked. Add the cost of building and equipping a bare-bones winery—at least another $250,000—the recurring costs of wine production, and the salaries of two to four employees, and you’re out somewhere between $2 and $3 million before a single bottle is sold,” wrote Patterson. “Urbanists can produce more or less the same quantity and quality of wine for less than $100,000, and then put the income back into the next year’s expenses.”

Though many consumers associate wine-tasting with bucolic rolling hills and gnarled vines, the 44th Street Wineries have discovered that Boiseans like the experience of sampling Idaho wines without making the trek out to Sunnyslope.

“There’s something wonderful about going out to the vineyard and having the experience of being out there and tasting wines in the vineyard and looking at where the fruit is from,” said House. “But we’re only 45 minutes away so we still can give people the opportunity to go see those grapes, but they can also taste wines, enjoy wines, closer to home.”

And the grittiness of Garden City doesn’t seem to be a drawback, either. Since the tasting room was completed in August of 2013, the 44th Street warehouse has hosted a number of private events, including a handful of weddings.

“Definitely people are surprised by the space here—coming into the warehouse district of Garden City and walking into our warehouse and seeing how beautiful it is,” said Krause. “It is sort of the stereotypical romantic experience to taste wine here and yet not be in the vineyards.”

Not to mention, a tasting room that houses three brands is ideal from a marketing perspective.

“They get the benefit of the marketing that we do and we get the benefit of the marketing that they do,” said Sullivan. “So it’s just a very symbiotic relationship where three companies that make wine and one company that tests wine are all focused on super high quality.”

And so far, the arrangement seems to be benefiting all parties. Over the last eight years, Cinder has upped its production from 44 cases to 4,500. The winery has also received a number of awards, including a gold medal for its 2011 Dry Viognier at the Sunset International Wine Competition. Coiled is also no stranger to awards. The winery’s 2012 Dry Riesling won Double Gold, Best in Show and Best White at the 2013 Idaho Wine Competition. And Telaya is also growing at a rapid clip—from 600 cases in 2012 to 1,600 cases in 2013. And this year, the company hopes to release 2,200-2,500, if they can find the fruit.

“At some point we’re going to exceed the capacity of the building and then it’s going to make sense for one of us to leave,” said Sullivan. “Right now, I’m the second largest in here so … it’s probably going to be me that they’d ask to find another spot. We’re thinking we probably have two to three years, but it depends on how fast everybody grows and what efficiencies we can put into this facility.”

But in the meantime, the 44th Street Wineries are barreling forward. Rocking her infant in a pram, Coiled business manager Kelly Marx poured a taste of the 2010 Sidewinder—a velvety, peppery red— which she paired with a bite of calabrese.

“We’re all a big family here. Even though we’re competitors, we’re like an extended family,” said Marx.

44th Street Wineries

Cinder Wines | @cinderwines

Telaya Wine | @telayawine

Coiled Wines | @coiledwines

House of Wine

The Southeast Wine Collective

Wines & Vines

Sunset International Wine Competition

Idaho Wine Competition