Honoring Our Past

Lewiston area winemakers push for recognition of Northwest’s pioneering wine region

A wine’s noblest aspiration, it can be argued, is its expression of character from the place where it was grown. And the finest of those places have names. Names that even the most casual wine drinker knows: Chablis, Chianti, Rioja. For almost 300 years, European countries have codified these names and places, known collectively as appellations, into law. These laws formally recognize the superiority of specific regions for the quality of the grapes grown, its winemaking with the added value of protecting their heritage.

The United States caught on to the value of this practice and instituted its own system in 1978. It is based on what is called an American Viticultural Area (AVA), defined as “a designated wine grape-growing region in the United States distinguishable by geographic features, with boundaries set by the Alcohol and Tobacco Trade and Tax Bureau (TTB).” (Notice that the TTB makes no mention of quality or superiority, just geography; more about this later.)

The Snake River Valley AVA was Idaho’s first, granted in 2007 and running roughly from Twin Falls in the east to Baker City, Oregon in the west, encompassing nearly 1,800 planted acres spread over 8,000 square miles. To the north, the Lewis Clark Valley—which is the Northwest’s oldest wine producing region—is poised to become Idaho’s second AVA, which some say is long overdue.

Wine in North Idaho had humble beginnings—a few acres of Royal Muscadine planted in Lewiston in 1864. These were the first grapes planted in the Northwest, well ahead of Washington and Oregon. By 1872, French settlers recognized the potential of the landscape and established vineyards and wineries that attracted international attention and critical acclaim. Among those early adopters may or may not have been Bordeaux’s most famous of wine families, the Rothschilds. By 1908, there were more than 40 varieties of grapes planted in the Clearwater Valley. But two years later the winds of Prohibition began to blow. By 1916 the state of Idaho went dry and along with it, the nascent Idaho wine industry.

And so it would have remained, at least in those parts, if not for the tireless work of the late historian, writer and professional weatherman Robert Wing. Convinced by Washington State University’s Dr. Walter Clore to plant a test vineyard in 1972, Wing applied his professional acumen for measurement to his new hobby, painstakingly recording every detail of each vintage. Over the ensuing decades he also researched and catalogued the history of wine in the Lewis Clark Valley, collecting and preserving records, photographs and newspaper clippings. It wasn't apparent for whom he was doing this until the early 2000s when a new generation of pioneers gravitated to the region.

“Bob Wing is so important as a link between history and the world today,” said Coco Umiker, a member of a long-standing farming family in the region. “But there’s a big difference between reading history out of book and having someone tell it to you, as if it’s their own story.” Over frequent dinners and numerous bottles of wine shared with Wing, the Umikers realized they were on to something big. “There was all this history, all this evidence of this potential, confirmed by Bob’s wines,” said Coco’s husband, Karl. "We realized all that was missing was someone doing something about it.” So they did, founding Clearwater Canyon Cellars in 2004.

From the beginning, the Umikers were convinced of the importance of an AVA for the Lewis Clark Valley. “Our goal is to make wines that rival the best in the country, and we are convinced that we can, but without the recognition that comes with an AVA, we’re just two crazy people making wine in the middle of nowhere.”

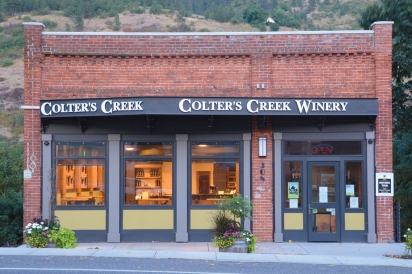

Mike Pearson and Melissa Sanborn were on a road trip from Moscow looking for potential vineyard sites when they stumbled upon what is now Colter’s Creek Vineyard and Winery outside the town of Juliaetta. Planted by Larry Spencer, a prolific grape grower and good friend of Wing, the vineyard had not produced fruit for seven years. Yet Pearson and Sanborn thought there was something special about it. Eight years later, that intuition has paid off. “Those that called us fools [are now] interested in planting grapes,” said Pearson. The Umikers report a similar experience at Clearwater Canyon. Coco likens it to “finding a geode that you’re sure has a crystal inside— and everyone else just sees a rock.”

Unfortunately, gut feelings and talk of crystals do not fly with the TTB. To establish the hard science and put it into language the government can understand, these four North Idaho winemakers retained the services of Alan Busacca, a Washington State University geologist with past success in AVA petitions. To fund the work, a grant was written with matching contributions made by local businesses and the shortfall coming out of the pockets of the wineries.

The theme of Busacca’s research, echoed in conversation with Pearson and Karl Umiker, is the distinct soil and climate of the Lewis Clark Valley (LCV). The area possesses more mollisols than any other currently recognized AVA, in Idaho or elsewhere. For those lacking a PhD in soil science, mollisols have deep, nutrient-rich surface soil high in organic matter. And everyone knows how much grape vines dig that. Vines also like heat, something the LCV has in abundance. Because the Valley contains the lowest point in the state at 750 feet elevation, it is hotter than one would expect given its northerly location. It’s just as hot as Washington’s Red Mountain, arguably that state’s premier AVA. Importantly, though, the LCV gets 15 inches more rainfall than Red Mountain and its numerous river canyons shield the vineyards from extreme cold and temperature inversions, which can shorten the growing season and damage the vines in winter.

These features of geology and climate directly affect what goes in the bottle. Pearson ripens and vinifies grapes, like Grenache and Mourvèdre, in the LCV that wouldn’t stand a chance in the Snake River Valley, increasing the diversity of the state’s offerings and thus improving its national and international exposure. This AVA proposal has it all: significant geographical distinction, historical precedence, plucky can-do wineries looking for some respect. But not everyone is sold on the idea.

As proposed, the Lewis Clark Valley AVA would cover approximately 306,000 acres, including 57,000 acres that are currently part of the Columbia Valley AVA, a fact that rankles some, namely winery owners whose properties occupy an admittedly small part of that 57,000. For the few grapes grown there, they would be forced to trade an established (and marketable) AVA for an unproven one. A possible alternative plan would see the Columbia Valley AVA expanded into Idaho; it currently stops at the Snake River. In this scenario, the LCV would then be designated a sub-AVA of the Columbia. This plan, however, is not supported by the science or the spirit of the current proposal and for now the fate of a border-straddling, independent LCV AVA rests in the hands of the TTB. Public comment ended on June 14 and was overwhelmingly positive. That means you may see “Lewis Clark Valley” on labels by next spring. Somewhere the ghosts of Robert Wing and wineries past are smiling.