Fishing the Redband

How to hook a native redband trout

Water flowed freely between two car-sized boulders, delivering a steady stream into a deep pool carved into the rocks below. The pool wasn’t quite eight feet across, but it was nearly 10 feet deep. Large sheets of granite lay across much of the stream and sheltered it from the blazing sun above, keeping the water cool and hiding unknown treasures in its dark waters.

On a boulder near the pool, my buddy Ryan McDaniel was lying on his side and casting his fly rod. A short burst of line shot from his Depression-era bamboo rod, which he whipped back and forth until the correct amount of line had been expended and the correct distance had been reached. It was a Norman Maclean-esque trout chasing moment, but in the Southern Idaho high desert.

The trout we were fishing have an interesting background: Columbia River redband trout are a close relative of the ubiquitous rainbow trout found throughout Idaho streams, but the Columbia River redband trout are wild and native. According to Chris Walser, professor of biology at The College of Idaho, Columbia River redband trout have been in the Great Basin area (the big bowl that contains most of Southwest Idaho and Northern Utah) for the past 50,000 years, which has allowed them plenty of time to evolve and adapt to the region’s climate.

Historically, Columbia River redband trout occupied inland waters east of the Cascades and below barrier falls (like Shoshone Falls). In the 1880s, fish management practices led to the introduction of the coastal rainbow trout. Some of the earliest fish hatcheries in the west began operation in California and figured out how to grow and disperse coastal rainbow trout throughout the United States.

“The introduction of coastal rainbow trout in Idaho is basically an artifact of historical fish management,” said Walser.

These hatchery trout were allowed to breed and, over the past 100 years, have passed their hatchery genes to the native redband trout.

“You don’t find genetically pure populations [of redband trout] unless you are in an isolated location—a location not historically stocked with hatchery fish,” explained Walser.

The heavily regulated South Fork of the Boise River, for example, has a sustainable population of large rainbow trout. These fish are wild, but carry the genes of hatchery trout.

I was seeking native redband trout, which is how I found myself on a tiny creek in the middle of the Owyhee Mountains. In order to avoid detection by the trout that lurked below, McDaniel wouldn’t stand on the boulder. Instead, he belly-crawled up to the edge to cast. A big shadow looming across the surface of the water is a sure sign that trouble is on the horizon.

Every few casts, McDaniel would drop his line onto the base of the waterfall, right where the falling water hit the pool. He then would quickly shorten his line and let his artificial fly, a small grasshopper imitation, float atop the water.

From below, a fish not quite eight inches long lunged itself out of the water to eat the hopper with ferocity. No novice, McDaniel waited for a few inches of line to disappear below the surface before he set his hook with a quick pop of the wrist.

“Fish on,” he uttered, but not too loud.

On the other end of McDaniel’s line was a wild trout, not the hand-fed version stocked in many waterways by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. Since it was young, this native fish had to fight for every inch in length and every scrap of its food. This fish was a survivor. And that is why the trout, small as it was, put up such a fight. The little pugilist showcased a wide variety of acrobatics—it skipped across the top of the water like a dolphin, dove like a steelhead and rolled like a sturgeon. Life for this fish had been a struggle and it knew how to fight. It was a wild fish.

Eventually simple machinery and larger brains won the day. After the fish finally gave in, McDaniel reeled him to the edge of the boulder he was crouched on. He grabbed his line and hoisted the little pan-fry onto the rock. A quick slice from a pocket knife and the fish was no more.

“One more and we’re set,” I said, watching the scene play out.

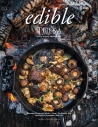

Soon I was hooked onto a fish as well—my much less graceful earthworm had worked. After both fish were eviscerated, we cooked them over a campfire. Wild onions and a little mustard gave these delicate-tasting, native fish a strong bite to complement their wild nature.