SYMPHONY OF THE SEED, PART III: THE SQUIRRELLING OF THE SEED

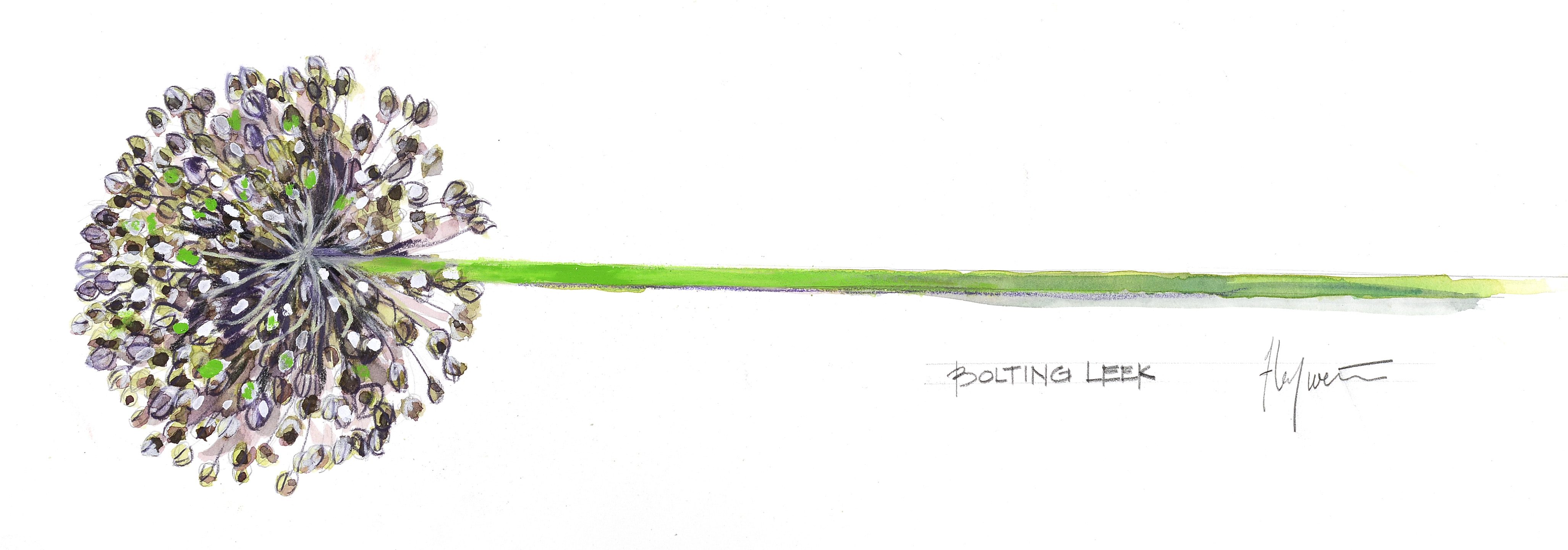

ILLUSTRATIONS BY FELICIA WESTON

The crescendo of summer’s relentless light and heat comes to a climax in dripping, swollen fruits that slip and slop their way from vine to table, overwhelming harvest baskets and gardeners alike with their bounty. Even the “worst” garden in September bears the burden of overabundance of some of its inhabitants.

While we gardeners curse the oozing piles of overripe tomatoes and baseball-bat zucchinis that demand our beleaguered attention, we cannot help but marvel at the facts: A handful of seeds made all of this! And every single tomato and pepper holds 100 more seeds!

This particular miracle of unfathomably exponential growth is enough to throw even the most miserly of humans into exuberant fits. Being a seed saver is like winning the lottery with every fruit. As farmer Eliot Coleman says, “At 1,000:1, you can’t get a better return than a tomato.” Eat your heart out, Wall Street!

Of course, this wealth extends beyond the fruits that hold ripe seeds when we harvest them to eat, like watermelons and tomatoes. The ultimate goal of all vegetables is to make seeds and, in fact, that’s what they’re aiming for when they grow a fat carrot root or a voluptuous head of lettuce. After a winter’s nap, a carrot plant will draw all that stored energy out of its taproot, pushing it upward into splashy, progeny-spawning flowers. Its root shrinks to a fragile anchor as it grows top-heavy with ripening seeds. The carrot plant summons all of its resources to concentrate its life force and wealth into thousands of tiny, nutrient-dense, spider-legged babies, leaving behind a shriveled plant to rot back into the ground.

If spring seeding and transplanting is a call to embrace vulnerability, fall harvest season offers the opportunity to contemplate selfishness. After a summer of incomprehensible symbiosis with a vast number of species and elements, the work of the harvest is noticeably human. We know only a tiny fraction about what made these fruits and seeds and yet we hoard them largely for ourselves. Moreover, these seeds are a product of centuries of doting human selection in concert with natural forces. Our ancestors noticed plants they liked better, with bigger seeds or fatter roots or sweeter leaves, and selected and crossed them over generations to transform wild plants into cultivated ones that better align with human desires. They are wild yet domesticated, just like us. One would not exist without the other.

And thus, we are inducted into the lineage of stewards of land and seed. We scurry around collecting as much as we are able to carry, can, dry, freeze and eat. We stuff dried seed heads into pillowcases, tarps and windrows, fending off the mice and the rain as the seeds dry down completely so we can thresh and squirrel them safely away. The rafters and the counters and every available flat, dry space fill up with curing seeds.

Sloppy piles of tomato and cucumber pulp fills every available vessel while microbes break down the gelatinous sack around the seeds that kept them from germinating inside their warm, wet fruit of a mother. After they ferment, we decant them with water—ripe seeds sink while immature ones and pulp float. We pour off the floaters and spread the plump sinkers on dishes to dry, then transfer them to neatly labeled jars. Tiny piles of seeds at the bottom of the jars grow larger as we work, until they overflow the brim.

The rhythm of threshing and winnowing seeds has fed souls as well as bodies for millennia. Percussive dancing on piles of dried stalks to free the attached seeds and then pouring them into the wind or shaking them through a screen links us in an ancient, unbroken chain of seed keepers. As we watch huge piles of dried stalks shrink to tiny handfuls of life-perpetuating seeds, the immeasurable satisfaction of this humble work comes full circle to feed us now and for years to come. We tuck them into rows of shelves in the cooler for safekeeping. As one high school visitor to my farm recently remarked, “Yo, hold up. this is life in here!”

In the presence of such bounty it is easy to see why cultures the world over have created rituals and prayers surrounding the harvest of seeds. the gluttony of squirrelling away a huge cache for ourselves is a necessary one, playing on our vulnerability in an uncertain winter and the year to come. Some amount of prudence and a hefty gratitude seems only right.

And like the seeds themselves, this acknowledgement of our interdependence sets us free. Free in the best sense. We belong to something as much as something belongs to us. What a cozy place to hunker down for a winter’s rest.