The Sleeping of the Seed

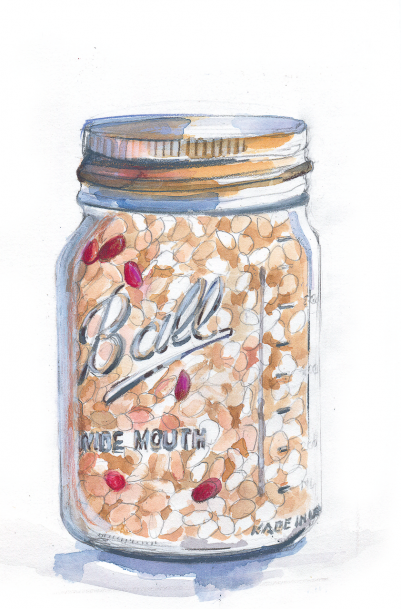

Even on the darkest days of winter, after the leaves have let go and the skeletons of trees shiver against the cold, life continues. As humans hunker down by cozy fires and bears hibernate in mountain dens, so too do seeds bide their time. Stuffed into jars in closets, burrowed into patches of bare ground, packed into sidewalk cracks, they wait.

Just as a rest creates excitement in a piece of music, the sleeping of the seed makes the sprouting all the more magical. But there are biological reasons for dormancy as well. A basil plant is a fragile thing—even the tiniest nip of frost and its cell walls burst, turning it to a black puddle of mush. So the plant summons the summer sun and creates thousands of durable seeds that can survive long after the first frost hits. Those seeds know their lives are at stake when they come undone and burst upward toward the light, so they wait until the time is exactly right, respiring only the tiniest of breaths to avoid using up their stored energy endosperm.

There are many reasons why a seed chooses to sleep rather than sprout. Obviously, if it is too cold or too hot, too wet or too dry, the tiny plant will not survive. In the desert, a single plant may make reckless daredevil seeds that will sprout the following spring regardless of conditions. It will also produce some that will wait for a year with decent spring rains, along with a select few that know the magic combination of environmental factors most likely to guarantee success, should it sprout. These jackpot-seekers can bide their time for decades, patiently watching the world go by until the odds are stacked totally in their favor.

Anchored in place, a plant cannot move. But seeds are portable. That portability catapulted angiosperms toward evolutionary dominance and made human civilization possible. If all the hundreds of acorn seeds produced by an oak tree fall on the ground and sprout right next to their mother, they’ll choke each other out or wither in her immense shade and none will live to reproductive age. But if they’re carried away from their mother in the pocket of an enterprising human or the cheek of a provisioning squirrel, suddenly their chance of success expands tremendously.

Seeds of all types have figured out just the right allure to entice animals of all stripes to spread them far and wide around the world. Whether in the digestive tract of an elephant or embedded in a fruit beloved by bats, seeds travel through the servitude of animals.

And here we arrive at the breathtaking climax of the human-seed story. Seeds not only allowed previously nomadic humans to stay put, but they also allowed humans to move. As grain seeds founded agriculture, humans organized themselves around their fields, feasting on the stored energy the sleeping seeds provided through periods ofdrought, cold or rest. They planted the bigger, more nutritious seeds that could sustain them for longer periods and different types of seeds that diversified their diets. Entire cuisines and cultures sprang up around the selection and replanting of seeds, and as humans became ever more mobile, they brought their beloved seeds with them.

Seeds traveled along trade routes between Native American nations. By the time Europeans reached the Americas, the unsuspecting wild grass teosinte had been turned to corn, and had traveled all the way from its native range in Central America tothe northernmost reaches of what would become the United States through the loving care of Native Americans. Hundreds of unique, locally adapted landraces of corn found their homes among tribes from Arizona to New York.

Hopeful European homesteaders loaded their ships and wagons with their favorite homegrown seed varieties as well, craving a familiar meal in a vast New World. Forced to leave their homes and cuisines, African slaves planted the seeds of their native foods in the Americas. Senegalese rice found a home in the Carolinas and okra has become synonymous with Southern cuisine. For centuries, refugees have carried hope with them on arduous journeys in the form of tiny, sleeping seeds.

After summer’s fleshy bounty, when we gorge ourselves on the houses for the seeds, in winter we eat the sleeping seeds themselves. Loaves of baking bread and simmering pots of chili keep us nourished through the darkness as we await the return of the light and the sprouting of spring once more.