Hunting the Wild Canyon

The Salmon River Breaks of Central Idaho are smoky in late summer. Wildfires in the Frank Church–River of No Return Wilderness fill a side canyon with the scent of campfires. Afternoon sun slants ruddy through the haze.

I arrive at an off-grid ranch where a saloon once refreshed gold miners when business in the canyon boomed in the early 1900s. A trio of sorrel mules graze irrigated pasture. A golden retriever bounds and barks beside the car. Dee Dog knows there are grouse to be hunted.

At the ranch house, Terry Myers fills a water bottle and tells me about grouse hunting in the canyon. “It’s like foraging. You walk for a while, maybe pick some berries, if you see grouse you take a shot. You almost never get to shoot a grouse in the air; they usually fly to a tree and disappear.”

The sorrel mules stay at the ranch—home to Terry, 60, and her husband Jerry, 63. They met on the Salmon River and raised their children along the waterway. The couple operated a wilderness rafting and fishing outfitting business for over 20 years. Now they boat, fish and hunt for fun and food.

The Myerses and I get in a four-wheeler, where Dee Dog has been waiting, eyeing the guns hanging behind the front seat. Jerry will use a .22 caliber rifle that belonged to his dad. Terry will use the 20 gauge shotgun her brother had as a youngster. “I don’t know why anyone would buy a new gun,” she says.

Terry started hunting at a young age, when her dad took her and her four brothers out to shoot ducks most winter weekends. She remembers, “It felt so alive that time of day, out with the animals, in the quiet. You’d be super in tune with everything around you. Your dog knew what you were doing and would be almost frozen in place, not moving.”

Terry’s dad never bragged about how much game he shot. “The only things he’d brag out was how much fun he had hunting with his kids: five kids in hip boots, carrying guns, out before sunrise in the winter. He’d have a big smile on his face when he told people.”

The Mule utility vehicle bounces up the east fork of the canyon, climbing past shrubs turning fall yellow under ponderosa pine. Farther up, dead trees stand, blackened by an earlier fire.

At a non-negotiable washout, we walk. I'm told to stay behind the couple’s guns. I look up in time to see a grouse cross open sky. Terry’s shotgun cracks, Dee disappears, reemerges, stops to spit feathers and delivers the bird.

The grouse is soft, warm and light enough to stay airborne. Jerry hands two feathers to me; later, I tuck them into the visor of my car with other storied feathers.

Later, climbing the west fork of the canyon, bighorn ewes and lambs cross the road. Jerry points out the widening drip line of oil marking the path of a sedan that was the worse for wear after encountering a rock.

Reversing direction, the Mule heads down canyon to a neighbor’s place, where Terry knows there are more grouse. I hike up a rocky drainage with Terry and Dee. The latter disappears when Jerry’s rifle sounds in the pasture below. With a second shot, he shoots a second grouse before we regroup.

Heading home on the Mule, Terry muses, “You do fun things because of your dog. You’re working and your dog wants to go for a walk. So, you go for a walk. Your dog wants to go hunting and you go hunting.”

We cut through the Myers’ home pasture, where cattle graze and are soon headed for family freezers. One wears a white heart on its forehead below curved horns. Terry spots a grouse, bounds from the Mule, shoots, and pulls even with Jerry at two grouse apiece.

When we get to a creek, Terry and Jerry skin and clean the birds, adding nutrients where steelhead and chinook salmon formerly contributed their bodies after spawning. The creek runs to the Salmon River, where Terry began a Steelhead Quest two years earlier. She fished a different river each month for a year with the goal of catching and releasing 12 wild steelhead. Her quest caught the attention of filmmakers, who recorded the adventure. Terry admits she has not caught her July steelhead yet; she and Jerry have a fishing date again next summer.

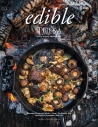

At home, Terry will soak the fresh grouse in saltwater to remove gamy flavors. Jerry’s birds from an earlier hunt have already been soaking so she simply breads and fries them for that evening’s meal. The garden’s potatoes and a ratatouille of canyon eggplant, yellow peppers and tomatoes join the grouse on the table. I find the grouse resembles chicken breast. Only the lime and coconut in the dessert flan are imported; the raspberry topping grew just outside.

Dinner was grown and harvested in the canyon where it is also eaten. I live upstream, along the Salmon River, where professionals grow my food. A community-supported agriculture (CSA) share, plus local eggs and meat, have provided my best-eating summer ever. I ponder growing and catching my own food and skipping the weekly drive to the CSA.

When the Myers' walk me out, Dee appears, hopeful, out of the dark. Downhill from the ranch, the waxing gibbous Corn Moon casts orange on the Salmon River as I follow it home.