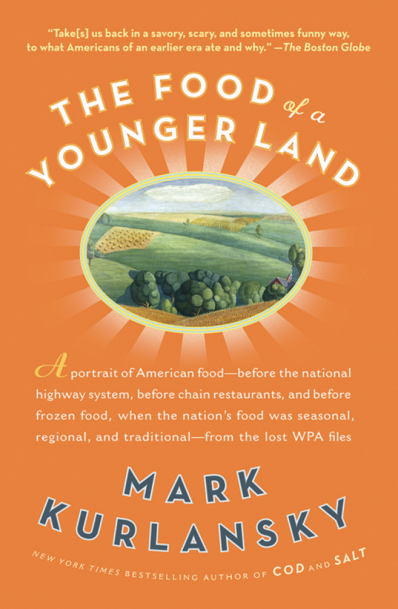

The Food of a Younger Land

These kernels of wisdom come from a chapter about Colorado superstitions in Mark Kurlansky’s book, complete title The Food of a Younger Land: A Portrait of American Food—before the national highway system, before chain restaurants, and before frozen food, when the nation’s food was seasonal, regional, and traditional—from the lost WPA Files. They were compiled for a project called America Eats, which was part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s massive Works Progress Administration (WPA) program to put unemployed Americans back to work during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

This group of writers, working under the Federal Writers Project, fanned out across the country to document food traditions and capture the social importance of preparing and eating food. Subjects were broad and came in many forms. Essays, poems, recipes and interviews all were included in the collection, which documented everything from fried beaver tail in Montana to lutefisk in Wisconsin to conch in Florida.

Weeks before the project’s regional offices were due to turn in their copy, Pearl Harbor was bombed and the country’s focus turned to war. The writers were reassigned and the America Eats program turned into the Writers’ Unit of War Services Subdivision. The project, and all of its unfinished writings, were scuttled away in boxes to the Library of Congress.

Kurlansky sifted through these lost WPA files to create a book that looks at a seemingly lost time in American eating. This was the 1930s, when regional differences were stark and pride for one’s culinary traditions ran deep. There were few chain restaurants. The country’s massive network of highways hadn’t been built. Freezers were uncommon. And high-volume, industrialized farming hadn’t taken root.

Divided by region, the Depression-era writings give the reader a glimpse of what cooking was like before the rise of high-tech equipment, fast-food restaurants and celebrity chefs. Recipes are loose with measurements but very particular about the end product. It was a much more intuitive and instinctual way of cooking. No sous-vide machines. No digital scales. Butter was measured in knobs.

In the “Far West” chapter, which covers the Pacific Northwest as well as the Rocky Mountain region, writers detail everything from large, community-wide salmon cookouts to bootleg liquor to cured wild game. They also devote a chapter to Boise’s Basque population:

“At the annual Sheepherder’s Ball, where dress clothes are prohibited and denim overalls quite the thing, the feasting is attended with dancing their own folk numbers, as well as American and Spanish dances,” Raymond Thompson observed in his entry “The Basques of the Boise Valley.”

Kurlansky points out a misconception that Basques came to the valley because it resembled their own landscape and offered sheepherding jobs that aligned with their own centuries-old traditions. “There were few full-time shepherds in the Basque provinces,” Kurlansky writes. “The recruits were simply farm people in need of work.”

Like writers from across the country, the men and women whose work was filed from the western office took pride in their region. At the time, the cuisine of the Pacific Northwest and Rocky Mountain states was viewed as inferior to that of the more affluent Northeastern states.

“The life of these people is not entirely one monotonous round of fried beans, baked beans, boiled beans, and just beans, varied only by an occasional jackrabbit or two,” wrote Edward Reynolds and Michael Kennedy in an essay submitted through the Montana field office. “Not as long as the creative ability of the Western people holds forth. . . . And until you’ve tasted jackrabbit mincemeat pie you have never appreciated the true brilliance of creative ability.”

The book doesn’t contain many photographs from the era, but a quick search through the Library of Congress website provides plenty. The images are striking and boast titillating titles. They show large community gatherings (“F.M. Gay’s annual barbecue given on his plantation every year”) and the massive amount of preparation that went into these large-scale events (“Cutting the forequarters of beef into 20 lb. hunks, Los Angeles Sheriff’s Barbecue). Others simply document wonderfully bizarre food moments (“Oysters and a political rally”).

It’s easy to romanticize this period of American food history, but it’s only one piece of a rich culinary tradition. While the landscape of cooking has changed tremendously, many of the same underlying values surrounding it have remained the same as they were during the time of America Eats.