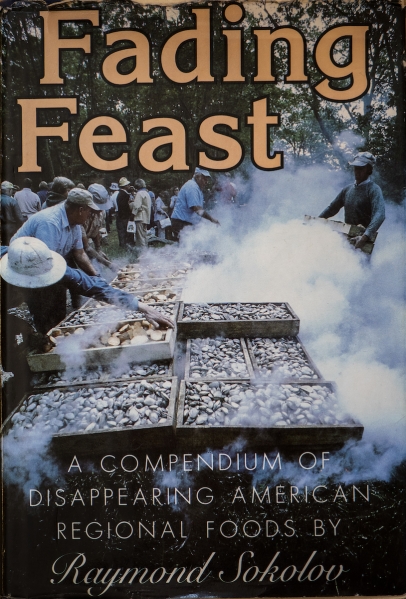

Fading Feast: A Compendium of Disappearing American Regional Foods

Writer Raymond Sokolov set out across the U.S. at the end of the 1970s to document regional food traditions. He thought much of the country’s individual identity was being wiped away by large corporations and a new social movement that seemed to value homogenization.

He traveled from coast to coast, on assignment for the American Museum of Natural History’s magazine Natural History, collecting recipes for regional specialties and documenting the culture and social structure around these dishes. Instead of a vapid culinary landscape, Sokolov found rich cultural traditions centered on food.

“We both assumed that corporate agriculture, Big Ag and all the other soul-crushing juggernauts of modern American life were smothering the last vital signs of regional food,” Sokolov said in a later book Steal the Menu: A Memoir of Forty Years in Food, referring to photographer Adelaide de Menil, who was traveling with him.

“But in almost every case, we found a dynamic revival of foodways, a supposedly vanished dish or abandoned ingredient that ought to have died out from neglect.”

Sokolov’s findings were collected as a series of essays and published as Fading Feast: A Compendium of Disappearing American Regional Foods. Each region has its own essay, along with a handful of recipes.

In Michigan, Sokolov writes about Finnish Cornish Meat Pies and includes a recipe for roasted bear paws. There’s an egglime soup in Key West, using the fabled limes. (Sokolov found that most Floridians actually used Persian or Tahiti limes in their regular cooking repertoire, not Key limes.) He covers lamb in Colorado, chiles in New Mexico, wild persimmons in Indiana, wild rice in Minnesota, boudin in Louisiana and clambakes in New England.

At the time, Sokolov thought these kinds of traditions were being subsumed into corporate food systems and shifting social norms that revolved around television, fast food and what he described as “hamburger culture.”

“This way leads inevitably to a radical loss of diversity,” Sokolov writes. But he also hints at a countermovement just budding at the time that strove to preserve diversity, smallscale agriculture and local food culture. “Only those with the capacity to grow their own food and the wish to follow their parents’ antiquated type of home economy can effectively combat the juggernaut of modern agribusiness.”

Sokolov’s essays still offer interesting glimpses into what the country’s food culture was like. Though he sometimes veers into folksy territory, his writing is layered with details and rich descriptions of these foods and the people who make them. He wanted to write about food, but he also wanted to delve into the social and economic impacts of that culture.

In the West, Sokolov touches on Native American cooking, mainly from the Hopi. He describes piki, a thin, crispy bread made from cornmeal. He talks about tribal members heating special rocks to cook the blue cornmeal batter, the special plants and ashes used to give the dish its distinct taste and color and the especially important step of greasing the cooking stones with a cooked sheep’s spinal cord before applying a paper-thin amount of batter.

“Piki was the most unadulterated example of all threatened American regional foods,” Sokolov writes in his memoir. “Enmeshed in the same civilization that had invented it centuries before Columbus.”

“That culture had survived under constant threat, first from the Hopis’ Navajo neighbors, then from white settlers and, by the time I came to their mesa villages, from electric flour mills and supermarket blue cornmeal.”

It’s in these cases that Sokolov revels. Even though he already seemed fairly jaded and cynical about the nation’s foodways, Sokolov found hope in cultures such as that of the Hopi. He found that it was the people surrounding these ingredients and ways of cooking that really mattered, and still do.

“The wild, red-faced revelers at Terlingua,” Sokolov writes in Steal the Menu, “like the downmarket mutton-barbecuing Catholics in Kentucky and the Dogpatch, Virginia, moonshiners were doing their part to uphold honorable food traditions, even if it meant risking trouble with the law in locations you wouldn’t want your daughter to visit.”

Raymond Sokolov

Steal the Menu: A Memoir of Forty Years in Food

Adelaide de Menil

Fading Feast: A Compendium of Disappearing American Regional Foods